Johnson Matthey (JM) has long made a good business monetising fallen asteroids, or rather the metals inside them.

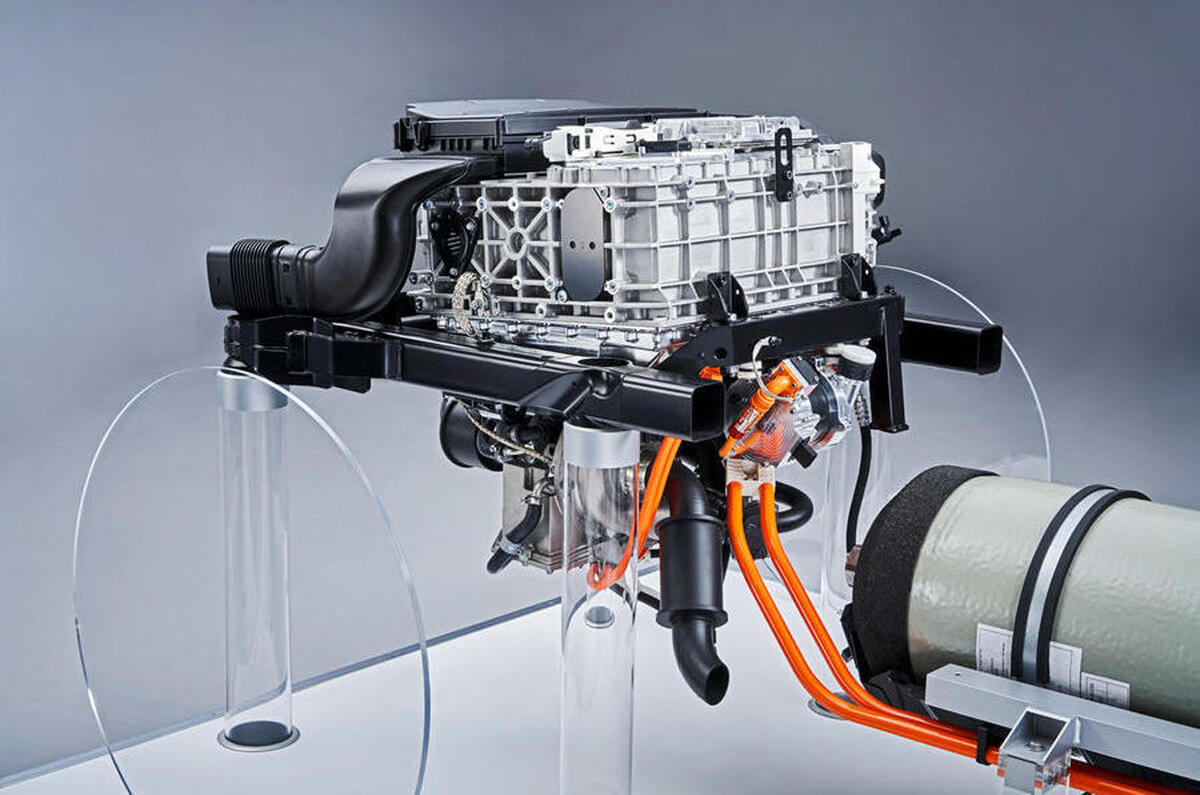

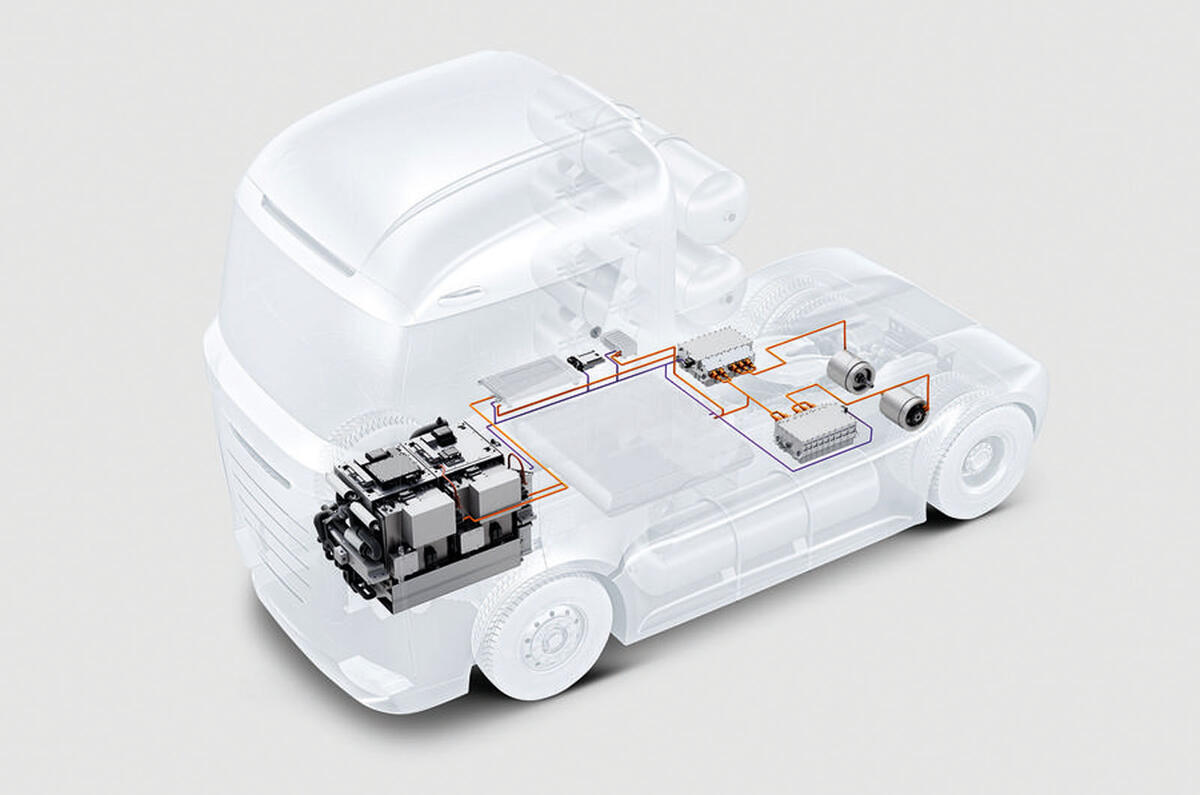

For much of the past half century, this 200-year-old-plus British company has used those metals to help reduce emissions on vehicles by making catalytic convertors. Now it wants to pivot its know-how of so-called platinum group metals to ramp up its zero-emission fuel cell business, targeting primarily heavy trucks. This would have been a neat transition if it hadn’t been for the company’s aborted attempt to get into the battery materials business, which ended back in May with a £50 million bill and some hurt pride after selling its operations to Australian outfit EV Metals.

Add your comment