It could be expressed in a thousand different ways just how much faster cars have become since 1928.

Rather than compare the top speed of the Austin Seven, subject of Autocar’s very first road test, with that of its modern-day equivalent, for instance, let me instead offer you this: early in 1928, the land speed record stood at 207mph. In 300,000 years of human history, it was the fastest any person had travelled while still in contact with the surface of the earth. It took Blue Bird III, a 24-litre aviation engine, the flat sliver of land that is Daytona Beach in Florida and the skill and bravery of that totem of human endeavour, Malcolm Campbell, to achieve it.

In 2018, any one of us who can afford to do so can walk into a Bentley showroom and buy a car that is capable of exactly the same top speed. Today, the luxurious, opulent, fully warrantied and entirely undemanding Continental GT is capable of reaching the same terminal velocity as the very fastest wheel-driven machine mankind had yet devised in 1928. That is how far road car performance has come in 90 years. The better part of a century of steady evolution – as well as the odd quantum leap forward – in engine, transmission, tyre, aerodynamic and safety technology has conveyed the human race from there to here, so cars are faster in every conceivable measure by an order of magnitude.

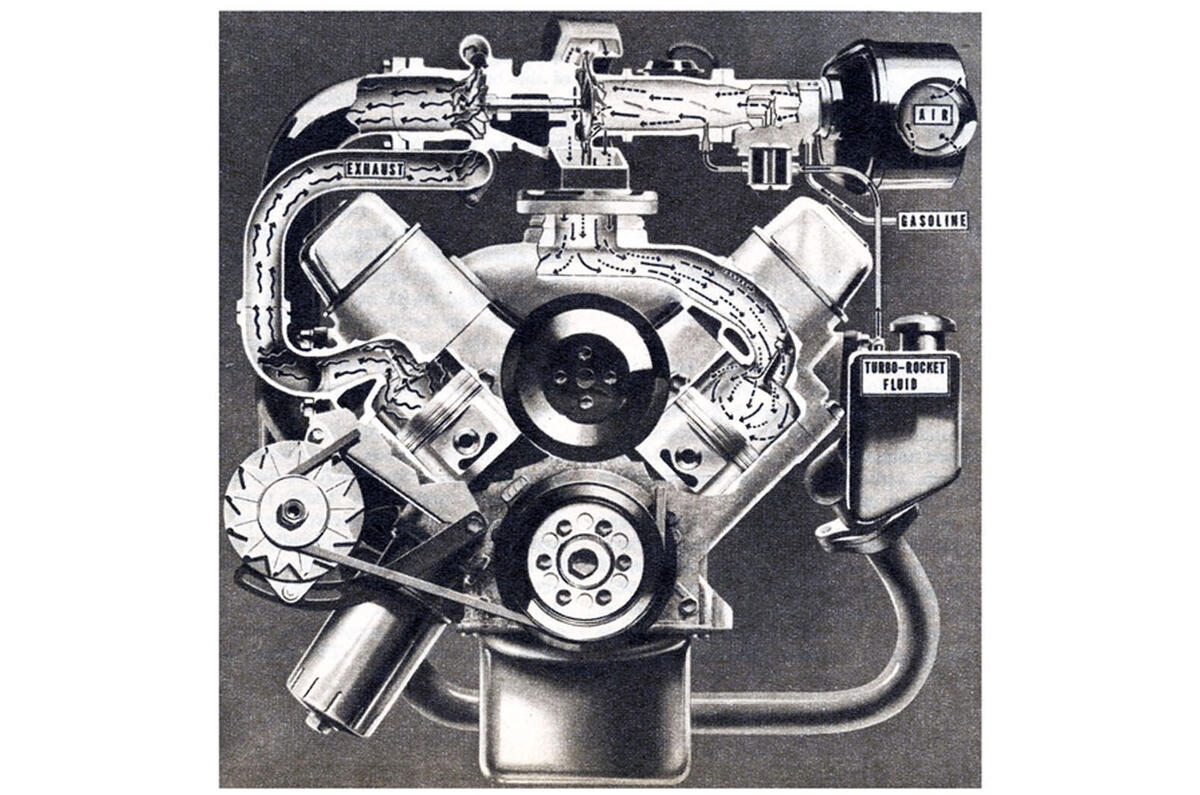

The forward strides that have been made in engine technology alone are enormous. It was in 1921 that a General Motors research laboratory discovered the effectiveness of tetraethyl-lead (leaded fuel to you and me) at reducing engine knock. Over the following years, leaded fuels were refined and engineers were able to crank up compression ratios. As a direct result, fuel efficiency and outputs shot up, and it would be decades before leaded fuels were phased out on environmental and public health grounds.

In the decades that followed, engine innovations continued to rain down. Variable valve timing, electronic engine management hybrid powertrains have helped to improve and, more recently, power outputs while also reducing the amount of fuel being burned.

Of course, massive progress has also been made in transmission and tyre technology since 1928, all of it helping to make the world’s most exotic cars faster than ever and everyday cars much quicker than any Austin Seven driver could possibly have imagined.

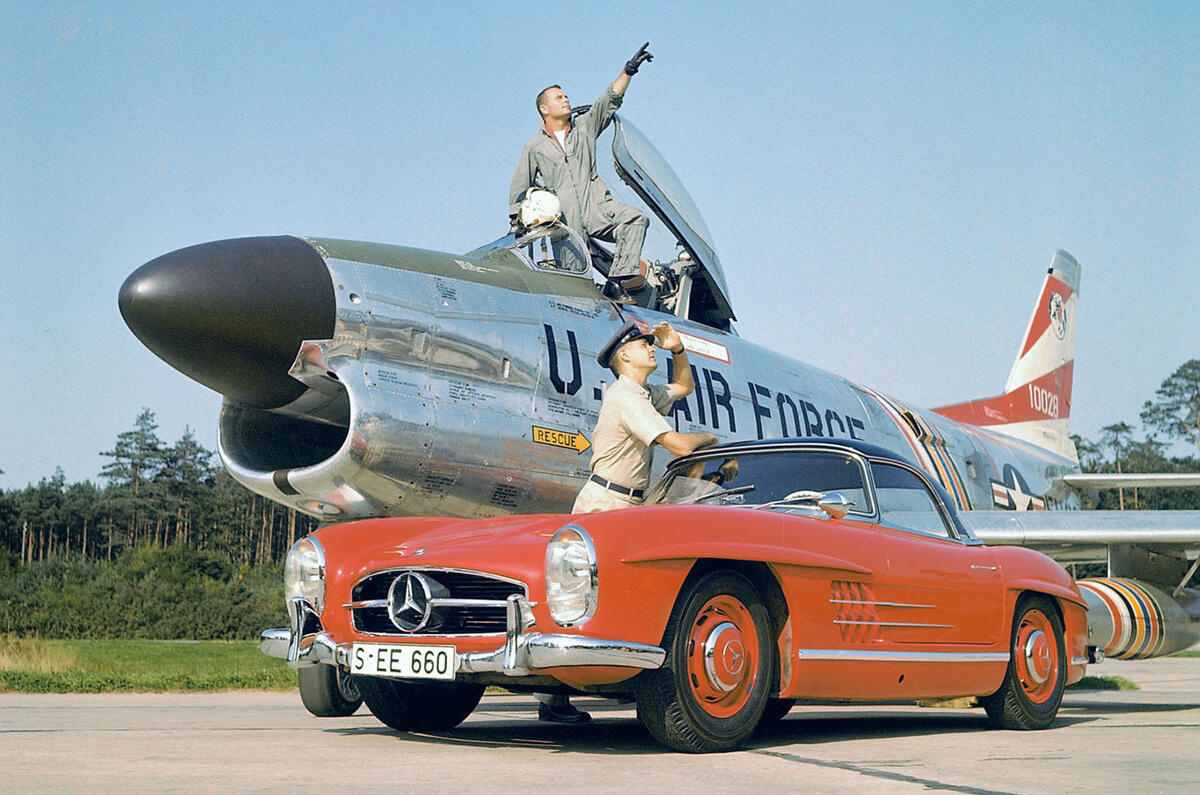

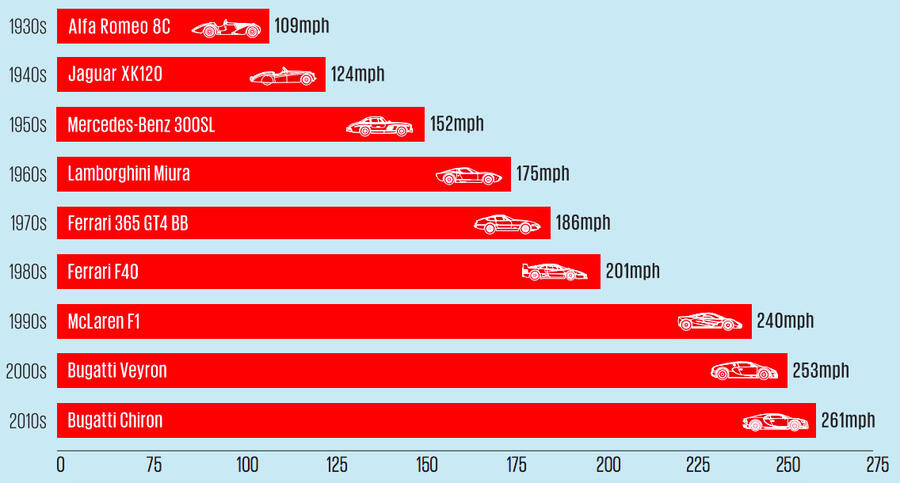

The 1955 Mercedes-Benz 300SL may have missed out to the Goliath GP700 on being the road-going pioneer of fuel injection, but it was a groundbreaker nonetheless, capable of 152mph flat out. That record would subsequently be raised by the likes of the Ferrari 365 GTB/4 Daytona, the McLaren F1 and the Bugatti Veyron as power outputs climbed ever higher, while the forthcoming Aston Martin Valkyrie is sold on the promise of far greater on-track performance than that of any other road-legal car.

The Bentley 61⁄2 Litre was armed with a walloping 6597cc straight-six engine to make it one of the fastest cars you could buy in 1928, yet it could only manage a top speed of 92mph. Progress could not come quickly enough. Today, however, we have surely come too far. Even the slowest Porsche 911 you can buy has 365bhp and can hit 179mph. Sports cars have become too quick for the increasingly congested roads they are driven on, and in this blinkered pursuit of ever-higher speeds and faster acceleration, driver engagement and interactivity seem to have been sidelined.

Cars have come a very long way since 1928, not least in terms of their performance. Today, however, it isn’t yet more progress that we need but just a little regress.

Join the debate

Add your comment

It could be expressed in a thousand different ways just how much

We provide eCommerce product listing, order processing, catalog management and product promotion services to online sellers. amazon listing services us

Performance doesnt need to

Performance doesnt need to evolve any further.

Most current cars can do 100+mph comfortably, and EV's acceleration is already so excessive that any improvement is meaningless.

Manufacturers should concentrate on the weak points of ride comfort, visibility & packaging.

Adding lead to fuel was a

Adding lead to fuel was a scandal and caused serious, widespread and unnecessary health problems.

Hardly the car industry’s finest hour and not something that should be brushed aside as an ‘innovation’ in the progress of the automobile.

History repeatig itself with the black stuff

Sounds familiar.