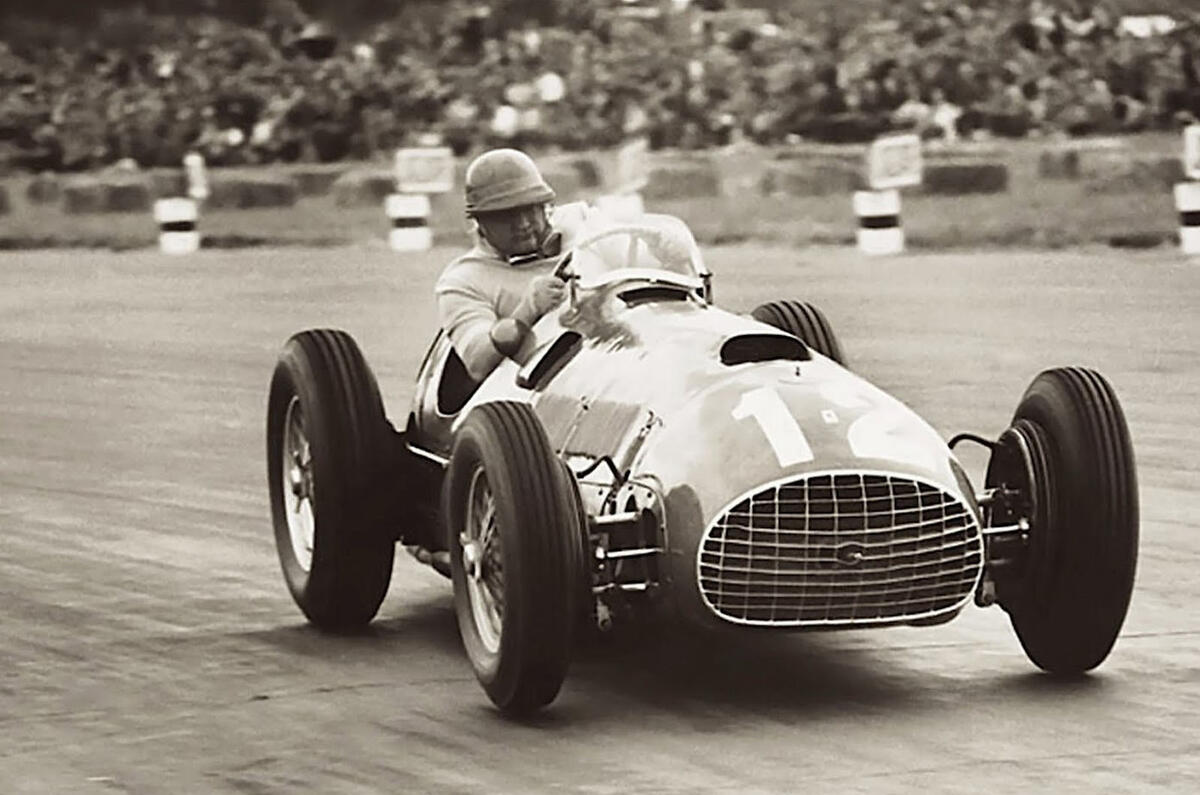

Seventy years ago this week, on 13 May 1950, a field of 21 disparate racing cars were fired up at Silverstone, setting off in a roar of engine noise and a cloud of exhaust smoke at the start of the British Grand Prix – and a new era of motorsport.

When Giuseppe Farina crossed the finish line in his 13-year-old Alfa Romeo 158 after two hours, 13 minutes and 23 seconds, the 43-year-old Italian secured victory in the first round of the inaugural Formula 1 World Championship for Drivers. It was the first of three wins from seven points-scoring events that would make Farina the first winner of the title that’s currently held by Lewis Hamilton.

Of course, a lot has changed in the seven decades between Farina’s win at Silverstone and Hamilton’s most recent title. Early F1 machines weren’t cutting-edge technological marvels but pre-war racers that had been dusted down and lightly modified. The Silverstone that hosted the 1950 race wasn’t a world-class facility but a bleak, abandoned RAF airfield with a circuit marked out by straw bales and rope. And 120,000 fans crammed into the venue, something that seems positively unthinkable at this stage of 2020…

But look closer and you’ll find that a lot hasn’t changed. The grid even then featured the greatest drivers of the era. The cars, while ageing, were the fastest and most spectacular racing machines in the world. And those 120,000 caused massive traffic jams heading into and out of Silverstone.

Most significantly, the grid mixed plucky independent British teams and well-funded manufacturers – Alfa Romeo, Maserati and Talbot-Lago in this case. And, as in the current age, it was those manufacturers, happy to spend money freely and exert their influence to bend the sport to their needs, that dominated. Heck, Ferrari even boycotted the race in a row over the prize fund; 70 years later, the Scuderia is still squabbling with officials over money.

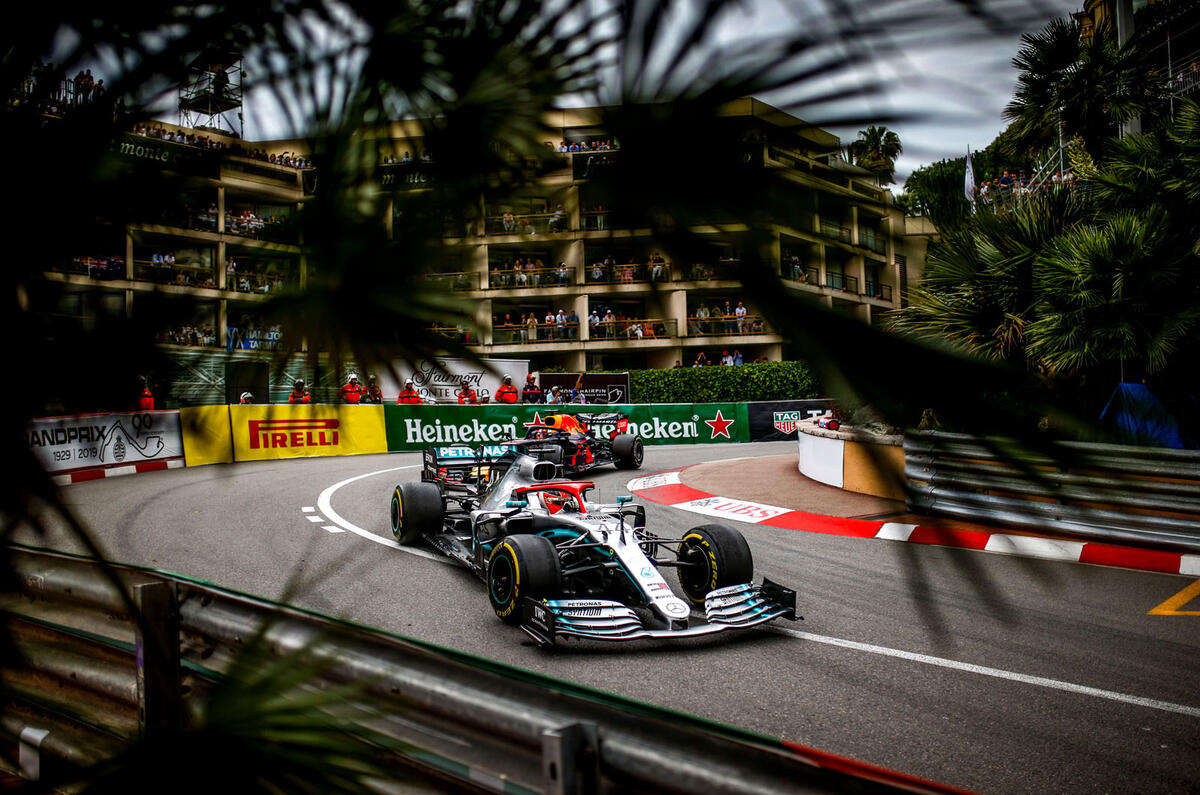

In its 70 years, the F1 World Championship has grown exponentially to become one of the world’s most popular sports – and an industry worth billions of pounds. Throughout that period, it has maintained a strange, strained relationship with the car industry. Manufacturers enter the sport, try to use it for their needs and then leave. Alfa Romeo won the first two titles and then quit. Mercedes-Benz arrived in 1954, dominated the 1955 season and then left, only returning as a full constructor again in 2010. Through the years, the likes of BMW, Ford, Honda and Renault have won races or championships either as an engine supplier or a full constructor. And other major firms, including Peugeot, Lamborghini and Toyota, were lured in, spent huge sums and left with little to show for it.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Car firms?

It seems quite simple "car firms" are engineering companies at their hearts (perhaps that's a little naive these days) and the engineering challenges are obvious.

Evidence would suggest car

Evidence would suggest car manufacturers are finding it extremely easy to resist the lure of F1.

And it requires an F1 apologist of the highest order to suggest that it has grown 'exponentially' for 70 years.

The peak was very obviously at least a decade ago, since when it has done pretty much everything wrong, culminating in these ugly cars powered by flymo/hoover hybrid engines that sound like farts.

Driven by Kevin Eason

I thoroughly recommend this book as a fabulous walk through the people and history of F1 by the Times F1 correspondent. I have no affiliation at all with the book or author but found it a right riveting read capturing the manoeuvrings of a certain Bernie Ecclestone and his peers. It's not really about the tech more about the fascinating garagistas of their day. Fantastic!