It’s summer 1931 and, since June, England has been enduring thunderstorms, flash floods and even the occasional tornado.

Thankfully, before autumn begins in September and the days begin getting shorter, there’s something truly exciting to look forward to, an event that will galvanise this rain-soaked nation: the Schneider Trophy seaplane race.

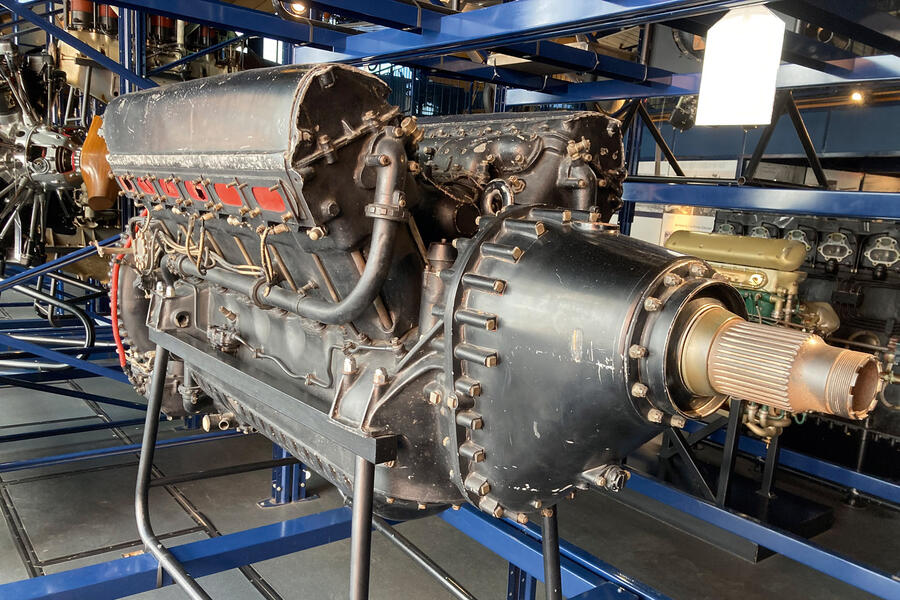

The first country to win the trophy three times in five years will keep it forever. Britain won it in 1927 and again in 1929, and now it stands to win it a third and final time, at least if the mighty supercharged 37-litre V12 Rolls-Royce ‘R’ engines powering our team’s Supermarine S.6Bs hold up.

The trouble is they are being tested to breaking point. They were used in the 1929 contest, when they produced 1800bhp and a winning speed of 328.64mph, but for the 1931 contest they’ve been boosted to 2350bhp. This has put a huge strain on them.

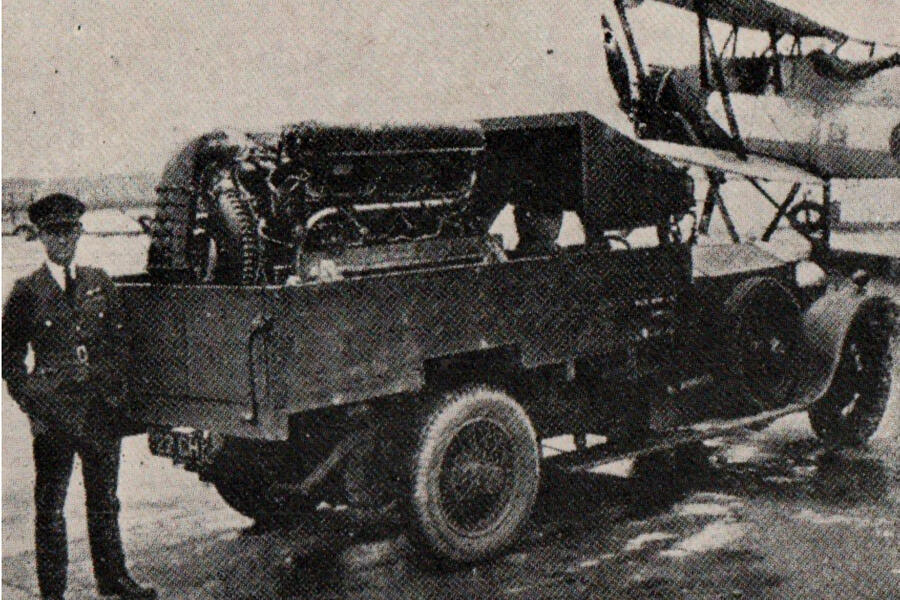

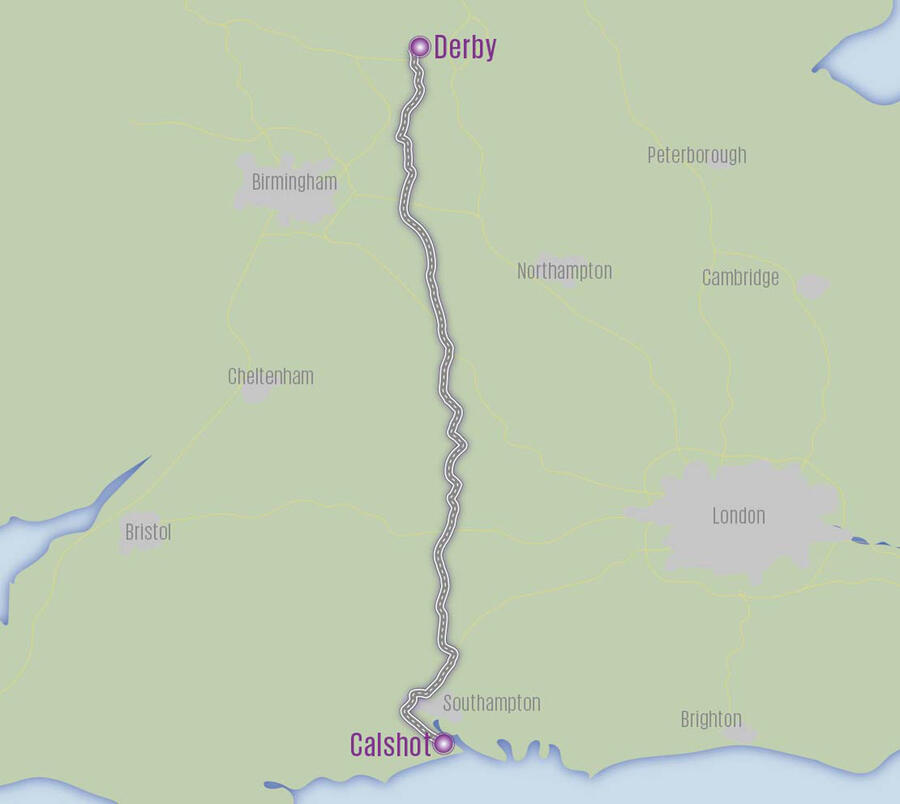

To avoid them self-destructing, Rolls-Royce advises that they are run for only a few hours before they must be returned to its Derby factory for dismantling, inspection and rebuilding using uprated parts.

However, 180 miles separates the company’s Osmaston Road site from RAF Calshot, on Calshot Spit beside the Solent in Hampshire, where the engines and the planes they power are being tested prior to the race in September. As the event draws near, every day counts. If the engines are to go to Derby, they must be back at Calshot and in the aircraft as soon as possible so that preparations can continue.

And then someone has an idea. For the greatest aero engines in the world, there can be only one means of transport: the greatest car in the world. That would be the Rolls-Royce New Phantom, otherwise known as the Phantom I.

Add your comment