Demand for battery-electric vehicles is set to grow rapidly in the coming years due to the need to cut emissions, driven by both government legislation and changing consumer expectations. But the move from combustion engine to electric power isn’t problem-free, given the huge amount of cobalt used in lithium ion batteries.

Cobalt is a key component of rechargeable batteries used in cars and smartphones, and around 60% of the global supply currently originates from mines in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Despite prices of the mineral soaring as demand surges, the estimated 255,000 miners in the DRC work in poor conditions, for less than £1.50 a day. According to reports, more than 35,000 of those workers are under the age of 14, earning around 60 pence per day. There are also concerns about illegal mining, human rights abuses and corruption within the country.

Late last year, 14 Congolese families filed a lawsuit in the US against firms including Apple, Google parent Alphabet and Microsoft. The families claimed that their children were killed or serious injured working in cobalt mines, that the named firms had knowledge the cobalt sourced for their products could be linked to child labour – and that they failed to regulate their supply chains properly.

In separate statements, Apple, Alphabet and Microsoft all said they were committed to responsible sourcing of materials.

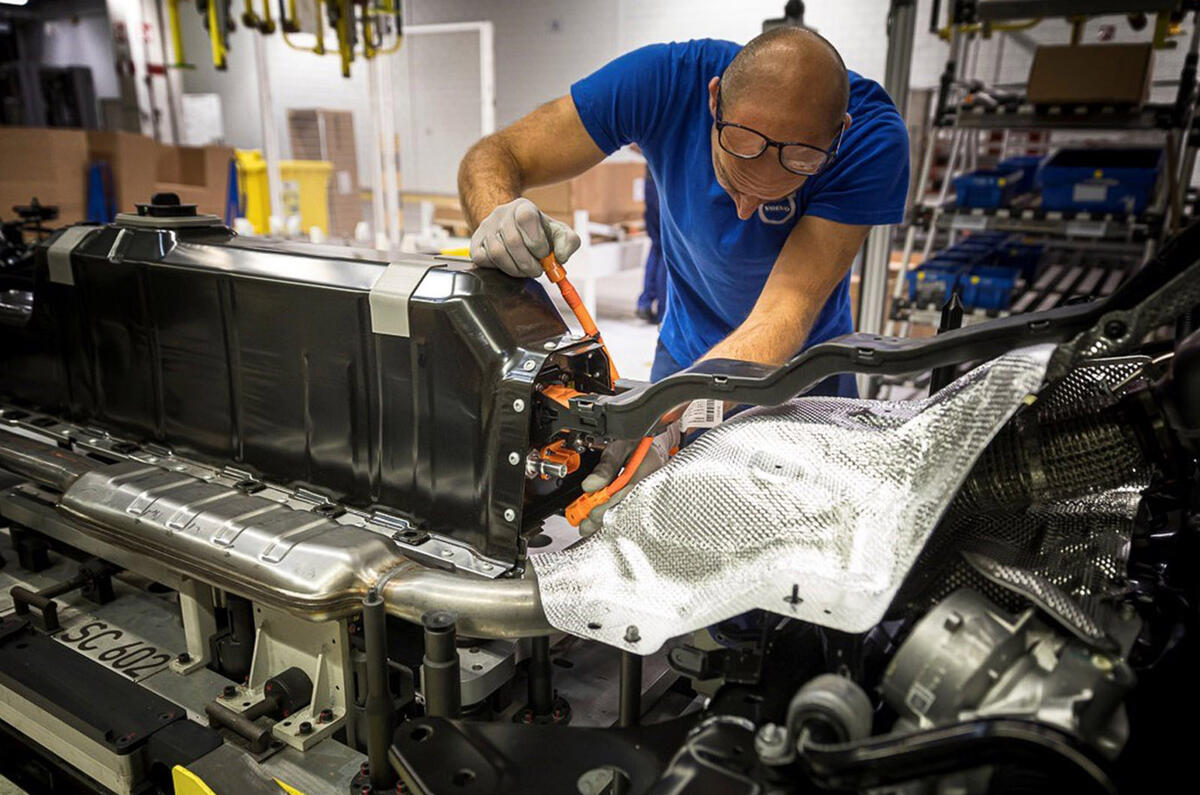

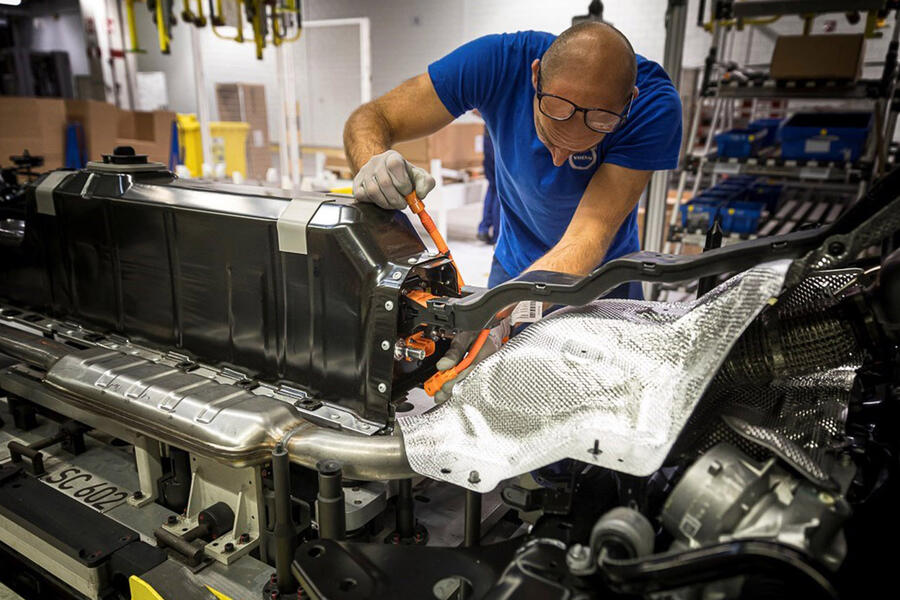

For car firms, ensuring cobalt and any raw materials obtained from third-party suppliers is ethically sourced is problematic – which is why Volvo is turning to new technology to do so. Last year, the firm announced it would introduce blockchain technology to ensure it could trace the cobalt used in the batteries of future Volvo and Polestar EVs, starting with the soon-to-be-launched XC40 Recharge P8.

The Swedish firm has worked with battery suppliers LG Chem and CATL on the introduction of the technology and recently invested in blockchain firm Circulor to aid the introduction of the technology.

“We already work with a non-profit in the DRC to help protect workers there,” said Martina Buchhauser, Volvo’s procurement boss, in a recent Financial Times online summit. “We’ve had it on our agenda to trace down where the cobalt for our cars comes from for a long time, but until now, we’ve been missing the technology to really do so.”

A blockchain is effectively a digital ledger consisting of a series of records, each linked to each other and protected by cryptography. It creates records for each transmission that cannot be altered, allowing for independent verification and auditing.

Join the debate

Add your comment

That's a bit hysterical.

That's a bit hysterical.

In 2019 Volvo sold something like 2.4% of the UK's new cars, so they can't be distorting the market that much. As for the "dime on the dollar" claim, that'd suggest that the true market price of an X40 should be around £300,000. Which seems unlikely.

Chinese Shill

Sporky are you a Chinese Shill? 2.4% is 2.4% more marketshare than they need to have.You simply cannot continue supporting such a corrupt unethical company that works off smoke and mirrors marketing to coverup their mishaps.Volvo- cant make seatbelts properly anymore.Volvo- Sues instagram user for using HIS pictures.Volvo- Reverse engineers model Y, then announces Polestar 3 is an SUV.Volvo- IP theft and chinese meddling all across the board.Boycott this worthless company.

Begone with Volvo.

Volvo have made themselves to be the enemy of all European manufacturers.

You simply cannot use chinese money to take food off the table of hard working, ethical Europeans!

Just cobalt?

This article concentrates on cobalt. I believe that there are similar issues with extracting lithium as well, and lithium is not that plentiful. With these sort of considerations, I'm not certain that the future for BEVs is as rosey as first claimed. I have read that hydrogen fuel cells might yet have their day, especially for anything heavier than a large SUV, including lorries and trains, but I believe also that these use rare or difficult to extract metals. There is also the question of the delay in implementing a decent supply infrastructure. Every potential solution will probably have its drawbacks.

streaky wrote:

streaky wrote:

There is not actually that much Lithium or Cobalt in EV batteries, Nickel and Carbon and much more heavily used.

Virtually all extractive industries have some level of issue at the point of extraction, the negatives are generally directly proportional to the poverty and corruption of the country where the extraction takes place and are by no means inhearant to the resource.

From an environmental perspective metal extraction also covers a really tiny proportion of the globes surface so is an acceptable trade off with room for improvement.

Pollution of generated by the ultisation of machines rather than by the raw materials of their construction is substnatially greater.