By the time the 20th century was becoming the 21st, Nissan’s Japanese bosses had become used to the sensation of desperation.

The company had travelled to the brink of existence by 1999 and bankruptcy had been fended off only by an audacious manoeuvre led by Renault’s Carlos Ghosn. The French manufacturer acquired a 37% controlling stake in Nissan for a life-saving $5.4 billion (£4.33bn).

What happened next is automotive legend.

Ghosn’s foundation-shaking Nissan Revival Plan turned the company around by doing the culturally unthinkable in Japan: shutting factories, breaking up cosy and costly ‘keiretsu’ crossshareholding arrangements with suppliers, making redundancies and more.

But it worked. In amazingly short order, Nissan returned to profit and started to produce desirable cars again, under the guidance of talented designer Shiro Nakamura. But not in every quarter.

Several less than scintillating cars were too close to the end of the development pipe to be scrapped or significantly altered. One of these was the second-generation Almera small family hatchback.

It was certainly an earnest improvement on the curiously barrel-bodied first-generation model, the interior of which was as inviting as a smashed bus shelter on a winter’s day.

The new version threw off the eaten-too-many-pies look, sported tail-lights as big as salad bowls and came with excitements such as shopping bag hooks, a loadsecuring net and more in-cabin nooks and crannies than a Cheddar Gorge cave.

It was also pretty tidy in the chassis department and had no serious flaws other than a rear leg room shortfall. However, the big problem was that it didn’t have the brand and showroom appeal of the Volkswagen Golf and Ford Focus.

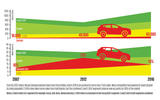

Once again, Nissan was left wondering how it would ever enjoy the heady success it had seen in the UK during the 1970s, when the Cherry and Sunny regularly appeared among Britain’s top 10 best-sellers.

Nissan’s Focus-chasing sales goals were receding like the unreachable refuge of a chase nightmare. But despite that, the company was masochistically lining itself up for a third pop at an Almera bullseye.

During 2002, its designers and engineers were hard at it, as product planning chief Pierre Loing recounted a couple of years later. But Ghosn, by now steering a robustly recovering Nissan, cancelled the programme in December.

Join the debate

Add your comment

HRV was the original crossover

Matra Simca Rancho was 30

Seriously?