The workings of some things are so bizarre that they can be almost unfathomable, and the rotary engine is one of them. Also known as the Wankel engine, pioneered by NSU and embraced by Mazda, it’s an alternative to the piston engine with no reciprocating parts at all. There are no poppet valves or valvetrain and therefore no need for chains, belts or gears to drive them.

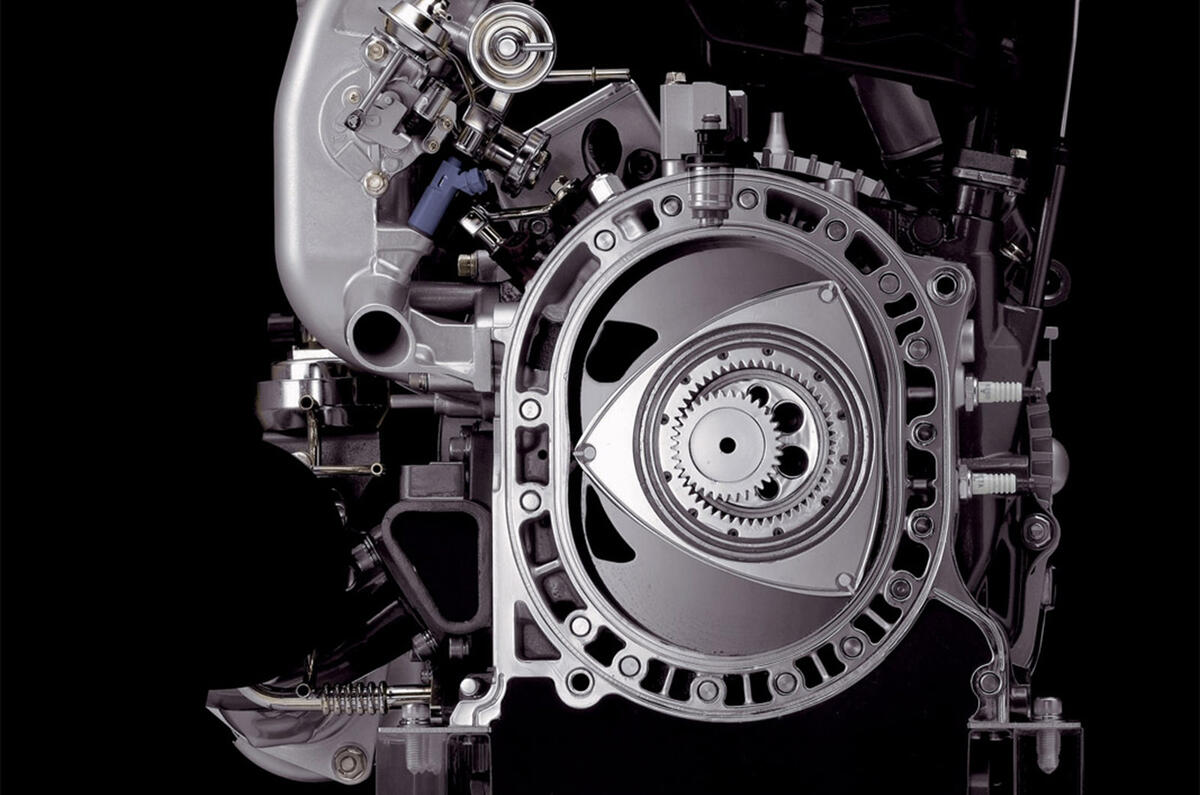

Inside the rotary engine, there’s a single, waisted chamber shaped like the number eight. Inside that, there’s a triangular-shaped rotor that looks a bit like a chunk of everybody’s favourite Swiss chocolate bar. Now this is where the name ‘rotary’ slips a little, because while it’s true that the rotor rotates, at the same time it follows a kind of oval path from one end of the figure-of-eight chamber to the other, like an orbiting satellite, spinning as it goes.

The rotor has a toothed hole at its centre that engages with a fixed gear to guide it accurately on its wonky path around the chamber. A crankshaft through the centre of the rotor takes the drive to the transmission, rotating three times for every single rotation of the rotor, due to the engine’s geometry.

Air enters and exhaust gas exits through ports that are opened and closed as the rotor passes over them, doing away with the need for valves. The movement of the rotor creates and squashes spaces between it and the wall of the chamber, and the changing volume of the spaces allows air in, space for expanding gases during combustion and exhaust gases to be expelled.

The rotary engine is one of the most hard-working of combustion engines, too. In a four-stroke piston engine, each piston generates power only once in every four strokes and two revolutions of the crankshaft. In a rotary engine, each single rotor generates power once per crankshaft revolution. The most common format is twin-rotor, generating power once every half a revolution, matching the bangs per rev of a four-cylinder piston engine.

When you put it like that, it’s easy to see why the rotary engine is such an appealing concept as a production engine. On paper, there are so many benefits, not least of which is a much smaller parts count than a piston engine. It can also run on a variety of fuels if need be. Frustratingly, though, there are some show-stopping flaws that have prevented it successfully challenging the piston engine.

One is that, like a two-stroke engine, rotary engines have total-loss lubrication systems, where the oil lubricating the apex seals of the rotor is burned in combustion, therefore increasing oil consumption and emissions. Thermal efficiency (the amount of fuel converted to mechanical energy rather than heat) is relatively poor, because of the area and shape of the combustion chamber. Fuel consumption is poor, too, and torque production is low.

Will we ever again see a rotary engine powering a car? Despite small size and great power-to-weight ratio, it’s unlikely. However, Mazda last year said that it will use one as a range extender in its electric MX-30, and possibly later in hybrids.

Audi's cloaks made of air

Join the debate

Add your comment

No hope?

I always thought that the only problem stopping the rotary engine becoming more mainstream was the well documented one of constant failure of its rotor tip seals. I didn't realised that in addition to the knowns of high oil and fuel consumption, its poor thermal efficiency is something that I guess that can never be rectified. OK - it's fabulously smooth and compact, but that clearly will never be enough, even for a hybrid.