Carbonfibre is one of those things that gets taken for granted as the super-lightweight material that costs a lot and few people can afford. But what is this stuff?

The answer to that is pretty much what it sounds like: fibres made of a graphite-like carbon. Those fibres are made from stuff called polyacrylonitrile (or PAN, a plastic), which in turn is made from acrylonitrile. The PAN fibres are heated at around 300deg C to burn off anything that isn’t carbon and then superheated to produce the carbon fibres.

That takes time and a fair amount of energy, which is why carbonfibre isn’t the most sustainable of materials – that and the fact that it can’t be recycled into high-grade material in the same way as aluminium can.

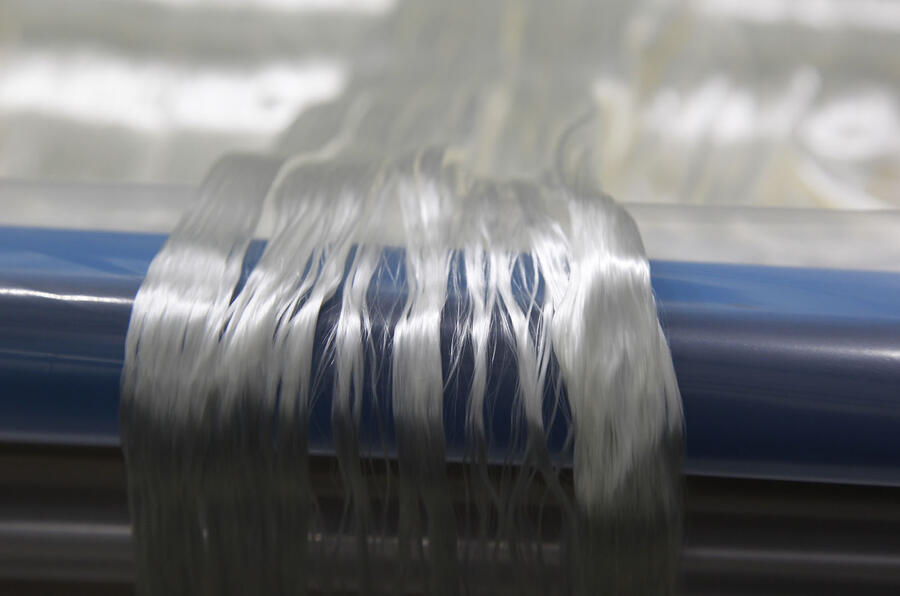

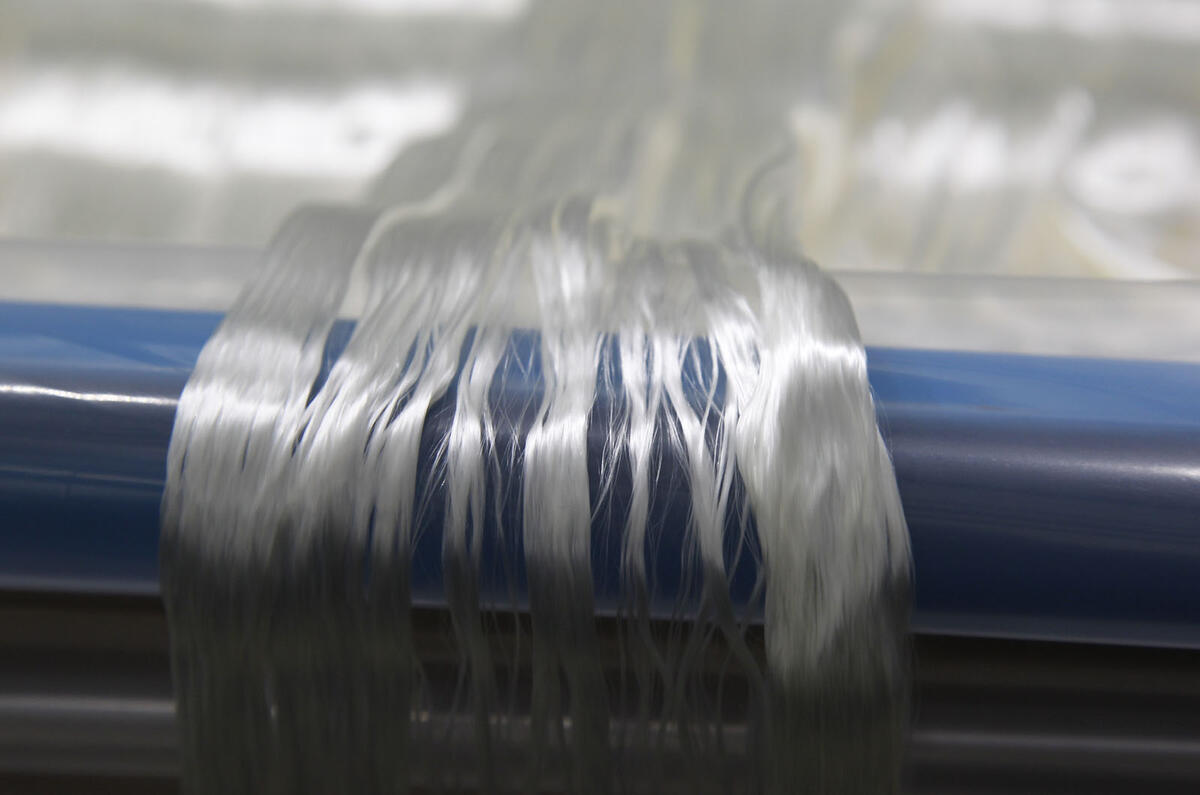

Wound onto large bobbins like some kind of elongated 21st-century cotton reel, the fibres are then woven into matting that feels much like smooth, rudimentary sacking but looks black and shiny. The weave can vary for different uses but the main types are called twill and plain weave.

At that point, how the carbonfibre is used varies. The fibre can already be impregnated with uncured resin and in this form is, not surprisingly, called prepreg. It must be cold-stored and, to use, it’s cut into the appropriate shapes much like a tailor would cut cloth for clothing. Then it’s ‘laid up’ in the mould for the component being made, the direction of weave in each layer decided by the engineers who designed the component. In a car’s main structure, like a Formula 1 or supercar tub, the direction of weave depends on which direction forces are working.

Next, the mould goes into a silicon-treated bag and the air is sucked out to compress the layers of carbon fibres together. Then the carbonfibre is ready for curing ideally in an autoclave (a pressurised oven) at 120-180deg C and 2-6 bar. That’s the way F1 car tubs are made. Where a megabucks autoclave isn’t available, then a bagged carbonfibre component can be cured in an oven (while maintaining the vacuum) at 60-100deg C.

A more expensive method but one used for the production of some car components and, in certain cases, complete car monocoques is a heated press. The moulds, or ‘dies’, are made of precision steel and similar to those used for pressing steel or aluminium body panels. Expensive steel tooling such as this is also used for resin transfer moulding (RTM), where the dry carbonfibre is laid up in the mould, which clamps together and is injected with resin at 10-20 bar and then heated. Once part-cured, the job can be fully cured in an oven later. RTM is fast and can be used to mass-produce several thousand parts a year.

One of the latest developments in carbonfibre is forged composite, where fibres are cut into short lengths of about 5cm, mixed with resin, injected into a mould and pressed (forged). More of that in part two next week, plus a look at who is doing what with carbonfibre and on which cars.

BMW’s high-fibre diet

Join the debate

Add your comment

Really??

Does this topic really need to be explained?? AutoCar's purveyor's are true PetrolHeads and have known about carbonfibre since it became the go-to material in F1 about when the Dinosaurs were killed off... Seriously?

we're not daft. nor ignorant

Yes, really...

So you know everything?, how did you find out things?, well, some of us ask obvious questions because we want to know.

And why not yet?

Carbon fibre has been around for decades and yet it is still expensive, you’d have thought by now that the costs of development and production would have come down by now, why?, can’t be the money, car makers just now are pouring billions into Battery development so why didn’t Carbon fibre get taken up in making cars lighter, stronger, safer?

Peter Cavellini wrote:

It *has* gotten faster and cheaper. During the 1990s, carbonfibre construction was only available in tiny-volume hypercars like the XJ220, F1 and EB110. In the early 2000s, it extended to high-end supercars sold in the low thousands, such as the SLR and Carrera GT. In 2011, McLaren brought it to the 12C, which sold for ~£150k at the rate of 1-2k per year.

Today, it's used in the £35k, 30k/year BMW i3. Which is kind of amazing.

Peter Cavellini wrote:

Yeah, I vealways wondered that, I think the answers in the article - the manufacturing process is quite labour intensive, but the article also mentions the new devlopment of "forging", which this, so we may see more of it in future.

They need to work on a resin that can be melted down or some other way that would enable it to be recycled though.

This series of more technical articles is great!

I've learnt something from most of them. Thanks!