California has long been a barometer for anything to do with emissions and air quality and has been since the 1970s.

For that reason it’s always worth taking any new developments emerging there very seriously. Since 1999 when it was formed, the California Fuel Cell Partnership hasn’t given up on its vision of establishing a hydrogen economy, even when others have.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has brought energy security into sharp focus, and the world (and not just the automotive world) is being forced to realise two things.

Everything you need to know about hydrogen cars

The first is that relying on one or two global regions for the majority of its energy supplies is a stupid idea, and the second is that seriously getting behind sustainable energy is a win-win situation. It solves the problem of energy security and CO2 at the same time.

In September, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) proposed the Advanced Clean Fleets regulation, which, if it becomes law, will ban the sale of new diesel trucks and buses by 2040. And while so much attention has been focused on whether or not hydrogen fuel cell cars will become a commercial reality, it’s as a power source for heavy vehicles that hydrogen as a road fuel is likely to take off.

The California legislature has committed to spending over £46 billion in the coming years to combat climate change (more, it says, than is being spent by entire countries).

Further encouragement to bring hydrogen into the mainstream in the US comes from this year’s Inflation Reduction Act, which will give a £2.52 ($3) per kilogram tax credit to producers making clean hydrogen from renewable electricity for a period of 10 years.

Unlike battery storage, there’s no physical barrier to using hydrogen to power not just heavy vehicles but also ships, trains and even aircraft. Universal Hydrogen has produced a hydrogen fuel cell electric conversion kit for the ATR72 and De Havilland Canada Dash-8 regional passenger aircraft, and it is set to enter commercial service in 2025.

At COP27 this month, the US Department of Energy announced its global H2 Twin Cities partnerships, which include the pairing of Kobe in Japan with Aberdeen, previously known as the ‘oil capital of Europe’.

The European Hydrogen Backbone, described as a ‘European hydrogen infrastructure vision covering 28 countries’ is a project run by 31 energy infrastructure companies from those nations.

Its latest update says a pan-European hydrogen supply network could emerge by 2030 connecting industrial clusters, ports and suchlike to regions of ‘abundant hydrogen supply’. Importantly, the network consists of existing natural gas supply networks and doesn’t involve installing new pipelines.

So while cars are no longer at the forefront of hydrogen power, the one thing that remained a barrier for so long, a global hydrogen infrastructure, is now taking centre stage. And while it won’t happen soon, it seems likely that the day of the hydrogen fuel cell car will come, after all.

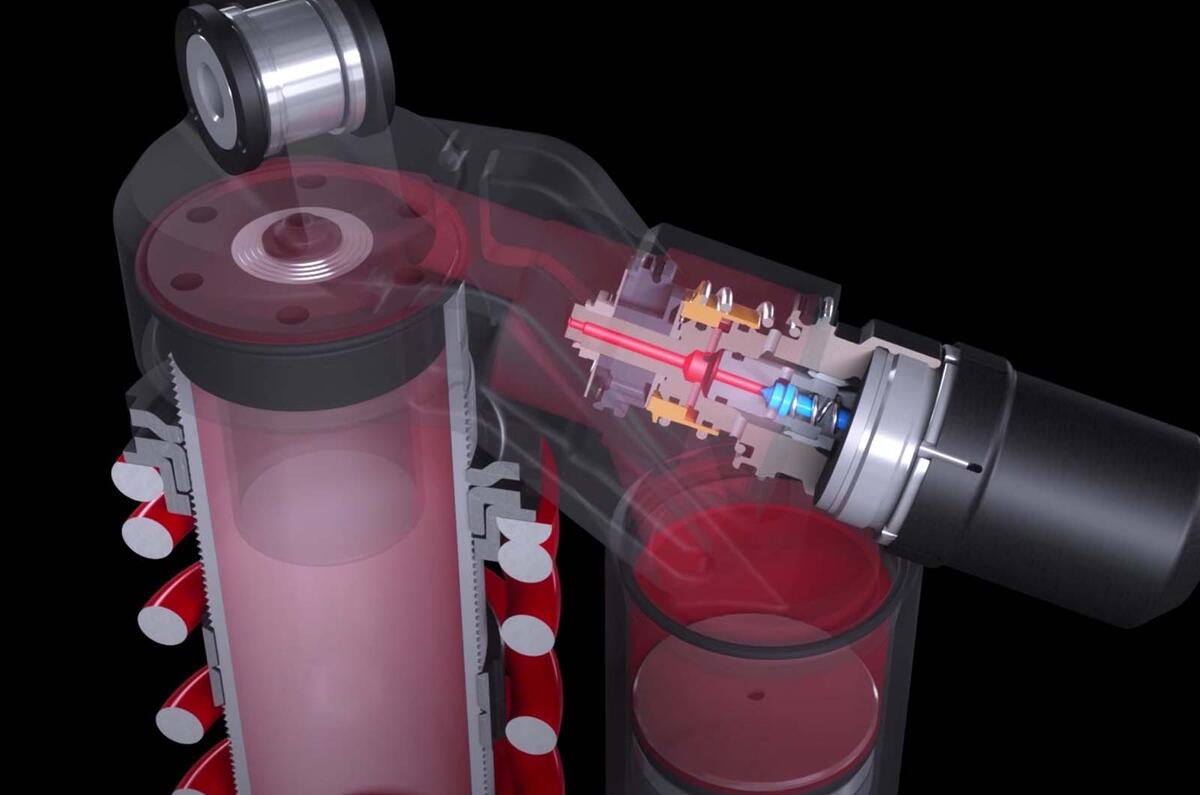

Damping technology on the new Ford Ranger Raptor

The Fox Live Valve damper tech on Ford’s new Ranger Raptor sticks to old-school hydraulics but uses a high-speed electronically controlled valve to increase or decrease compression damping on the fly. The technology has to make the fast changes to damping needed off road while still allowing the movement of relatively high volumes of fluid, given the size of the hefty dampers.

Join the debate

Add your comment

I'm afraid this article doesn't seem to see the difference between hydrogen being produced "greenly" for such as industrial processes (where it is used as a chemical), and hydrogen used as fuel for road transport. The former is a sensible project - the latter isn't. Likewise any move to hydrogen makes no difference to energy security. In the context of cars, it's purely a energy carrier - not source. The energy itself has to come from elsewhere to make it - either fossil fuels or renewable electricity. And it's far more efficient to use such electricity to charge a battery.

Regarding California, then they suffered from being too far ahead of the game. Twenty and more years ago hydrgen and fuel cells did indeed seem like the only way to (eventually) clean up exhaust emissions - batteries (then) simply couldn't be seen as being competitive in price or performance (charging etc). Times have changed. Battery performance is vastly superior to only a decade ago, and vastly cheaper. BEVs offer the same zero emissions as fuel cells but with a host of advantages overall. (Simpler and needing less maintenance, less bulky, and the ability to "refuel" at home overnight for just three.

Most people have now thrown the towel in on fuel cells for cars, even Shell has closed all it's filling stations for hydrogen in the UK now (leaving some of the few FCEVs effectively now useless) and stated they don't see any future for fuel cell cars. There is still talk of it for heavy vehicles, but there are now a lot of battery trucks coming on the market, and it's going to be a very uphill battle for hydrogen for trucks. (One advantage they previously quoted was range. But Tesla have now launched a Semi with 500 mile range, which is more or less what is being quoted for under development fuel cell semis.)

The article seems to confuse hydrogen in general with hydrogen fuel cell cars. Hydrogen is already widely used as an industrial chemical - the challenge is to make it in a green way. It's very misleading to then conflate that with it then making sense to use it for road transport. Likewise the point about energy security. Hydrogen in this context is an energy carrier - not an energy source. It needs the initial energy to come from elsewhere. If from fossil fuel (as mostly at present), how does that help with energy security? If from renewable electricity via electrolysis, it needs about 3x as much like for like as using the electricity directly for battery charging.

Autocar stop reprinting press releases and offer some journalism to your articles. IF our country has less than a handful of hyrdogen stations and all hydrogen currently supplied in the UK comes from Oil+Gas wells: this is not the Green News Event you are re-posting.

When I asked jim Holder if they are "News Agregators" he said they don't. Clearly a false statement. I am also p*ss*d off at "Business Subscription" extra cost requirements to read "Exclusive" stories when I am already a subscriber to the magazine.

The E.V. market is too far developed to make hydrogen viable as an alternative.

And yet no mention of the fact Shell have closed all their hydrogen stations down as they state there is no future for Hydrogen cars. I think the number of hydrogen stations open are now in single figures for the whole of the UK. Still that's more than the number of hydrogen cars sold per year in the uk.

Auto car must be paid for pumping up this overhyped rubbish