Enthusiasm for BEVs (battery-electric cars) is growing, which is a good thing. That said, no amount of EV enthusiasts telling consumers they don’t actually need the range they think they do will convince them to pay more for something that does less. Manufacturers know this, which is why there’s so much talk surrounding the latest wonder-tech looming over the horizon: the solid-state battery.

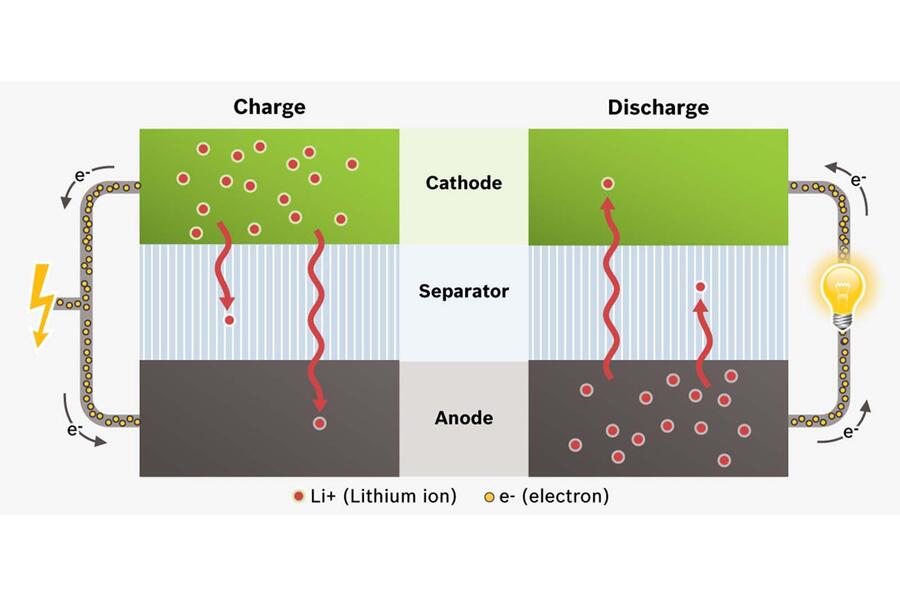

So what are these miraculous things that it’s claimed will banish any quibbling about range forever? The main components in any battery are electrodes (anode and a cathode) immersed in electrolyte. A conventional 12V lead-acid car battery contains a solution of sulphuric acid as electrolyte, which is fine as long as it stays in the battery. A lithium ion car battery has an inflammable electrolyte composed of lithium salts in a solvent. Lithium ion batteries have a further important component, too – the separator that keeps the electrodes apart.

If lithium ion batteries are not carefully controlled when in use, then heat build-up can cause ‘thermal runaway’ resulting in a nasty chemical fire that is impossible to put out. Because of that they need complex electronic battery management systems and equally fiddly cooling circuits to keep them safe, making manufacturing harder and piling on weight and cost. The upside is that lithium ion batteries are more powerful and store more energy than any other battery type. But they could be better still.

Solid-state batteries should overcome all those problems by switching to a non-flammable solid electrolyte, hence the name. Heat in a solid-state battery is easier to control so cooling is simpler, cheaper and less bulky, there’s no need for separators and a heavy, protective outer casing is unnecessary because the technology is intrinsically safe. The real barrier to getting them to work in the past was the poor conductivity of the solid electrolyte such as a ceramic material, but the latest materials are said by battery developers to be highly conductive.

The biggest bonus, though, is the energy density – the amount of energy a battery can store relative to its weight and volume. Claims for batteries capable of storing more than twice the energy of a conventional lithium ion battery are being made, along with reduced manufacturing costs. This simply means a solid-state battery will last longer and give an EV a greater range than a conventional battery of the same volume and weight. It’s that virtuous circle again. The lighter the battery, the lighter the car, the less energy it needs to achieve the same range, so the battery can be even smaller.

Car makers are talking about the technology being in production by 2025 and some sooner than that. When and if it happens, it would radically change the automotive landscape. Radically increased range would reduce the need for charging on the move, easing the pressure on infrastructure, because one overnight charge (for those with such access) could make the need to charge during a longer journey less necessary than it is today.

Inside a lithium ion battery

Join the debate

Add your comment

Range anxiety

I drove one of my regular routes into Central London and back yesterday in my BEV. I left home with 300 miles indicated and drove as I would have in any of my ICE vehicles (briskly, but not stupidly, as I have six points on my licence). My average speed was less than 45mph.

When I got back home I had done 125 miles, but used 200 miles of range, and so only had 100 miles indicated left. That doesn't bother me, but I'm not surprised many people are sceptical.

Longer range not always needed

Nice way of admitting the EV enthusiasts are right while not offending your petrolhead readership.

Improvements to charge density can be used to make EVs lighter, not just longer ranging.

There will be more cars line the Honda e, with a 35.5 kWh battery.

Taxation of road electricity

At the moment charging any EV is cheapbut once their numbers reach a certain critical mass the government in the UK and elsewhere for that matter will seek to replace lost revenue by taxing electricity for vehicles in the same way that conventional fuels are at present. Fuel tax accounts for a sizeable chunk of the government's revenue stream.