Modern civilisation revolves around crude oil.

Cars are one of the most visible uses for it, and therein lies the story of two brothers: petrol and diesel. They’re born of the same origin and differentiated by little other than the lengths of their carbon atom chains, yet diesel has a far dirtier (literally) image.

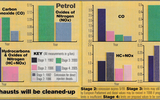

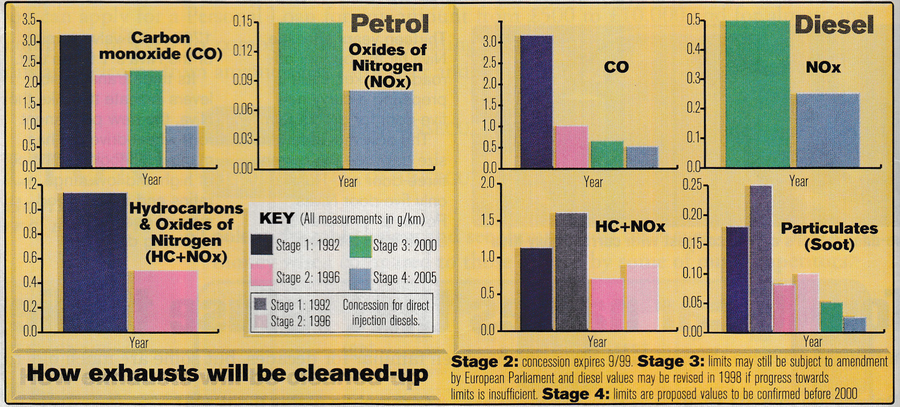

After all, it’s estimated that despite being more fuel efficient and producing less CO2, diesels cough out as much as 10 times more polluting soot particles than equivalent petrol-engined cars.

On 2 October 1996, Autocar’s Tony Lewin wrote about the uncertain future of the controversial fuel.

Health issues

“Diesel is set to become the environmental battle of the next decade,” we began. “Just as more car makers are turning to diesel power in order to meet stringent consumption targets, environmentalists and medical experts have come up with new warnings linking diesel particulate (PM) emissions with increased risk of respiratory diseases and cancer.”

In 1996, US Lung Foundation expert Mike Walshe said: “Diesel is hazardous because the small particles are drawn deep into the lungs and past the natural defence of the body" and that "evidence is emerging that new technology is making particles smaller, reducing their mass, not their number. This may make the health risks worse.”

Indeed, in 1988, diesel engine exhaust fumes had been classified as a ‘probable’ carcinogenic by the UN’s World Health Organization (WHO). In 2012, it confirmed that status, placing diesel in the same category as asbestos, arsenic and mustard gas.

At the time, Dr Christopher Portier, chairman of the group behind the research, said: “The scientific evidence was compelling and our conclusion was unanimous: diesel engine exhaust causes lung cancer in humans. Given the additional health impacts from diesel particulates, exposure to this mixture of chemicals should be reduced worldwide.”

In that year, the Institution of Occupational Safety and Health (IOSH) estimated that there were nearly 4700 cases of lung cancer, resulting in more than 4200 deaths, linked to diesel exhaust exposure in the EU.

Market share

Back in our 1996 article, Walshe said the most serious worry was “the rise in the number of diesel cars in Europe”.

Join the debate

Add your comment

These two quotes:

Interesting Story

Vehicle taxation is about to

However, you can guarantee that whatever the government decides in the medium term will be in no-one's best interests other than state coffers and be mired in incompetence.Incompetence,,,,