All of this means that while so many luxury vehicles desperately lack the calibre of steering necessary to explore their handling, the Ghost is different. And it is far from undone by interesting roads (although you may want to avoid any B-road rat runs). In tighter corners, there is no escaping the spectre of understeer, just as you would expect, and there’s zero throttle adjustability in this chassis, but the neutral-verging-on-oversteer balance the Ghost adopts in quicker corners is genuinely satisfying. And, of course, there is that deftly and accurate steering to underpin proceedings.

So, yes, the Rolls’ body floats much more than you’d find with any Bentley, and there is pronounced roll, however well it might be meted out. Yet for a machine supposedly all about the back-row seats, there are several good reasons why owners would take the wheel themselves.

It feels a bit rude to hurtle around Millbrook’s Hill Route in a car as stately as the Ghost, but it copes with this tortuous stretch of track well enough, given its immense size.

Body movements are, of course, entirely conspicuous, and you get the sense that its stability and four-wheel drive systems are working overtime to keep its nose tracking in the right direction. The threat of understeer is ever present. Even so, once its front end bites and mass has settled over its outside tyres, it navigates tighter sections of track with impressive neutrality and reassuring levels of grip.

The featherweight steering that makes the Ghost so delightful to manoeuvre at sociable road speeds takes some getting used to at pace and can sap your confidence a little.

Rolls-Royce might claim this is a car for driving as much as being driven in, and at relaxed speeds that rings true. What it isn’t, however, is a car for hustling along. Which is fine.

Comfort and isolation

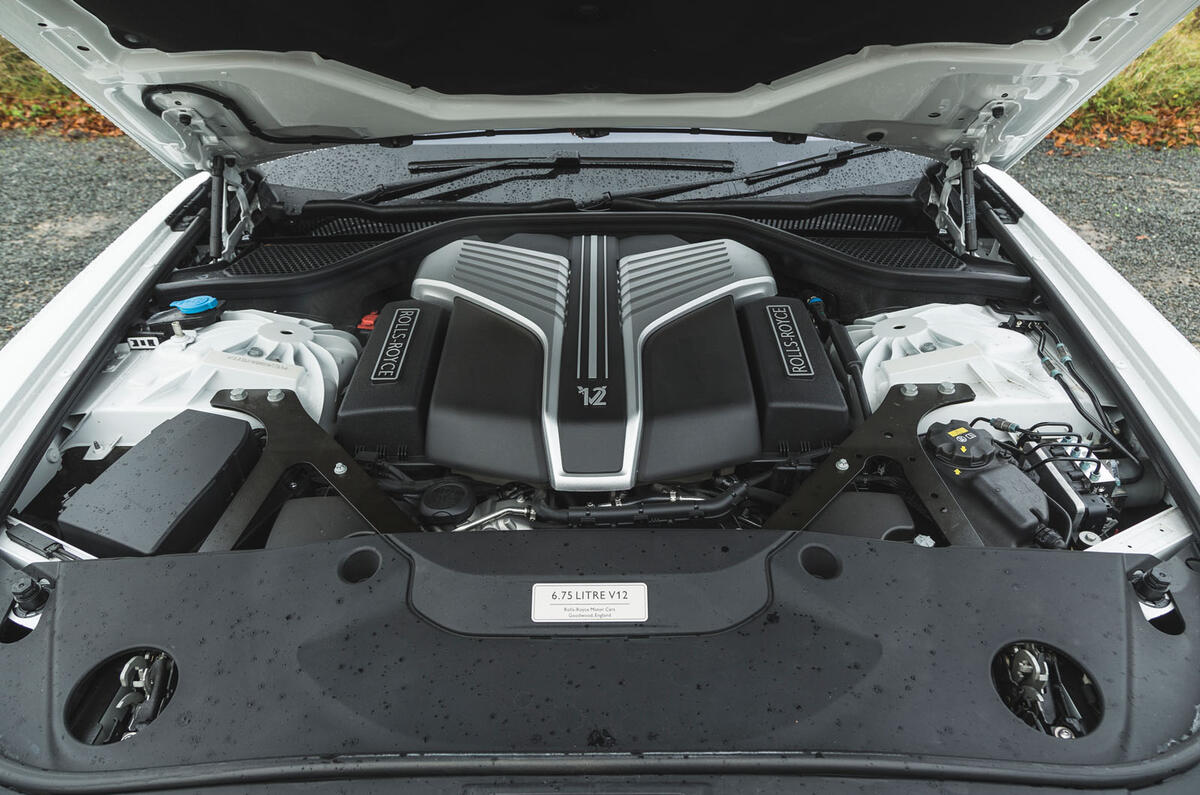

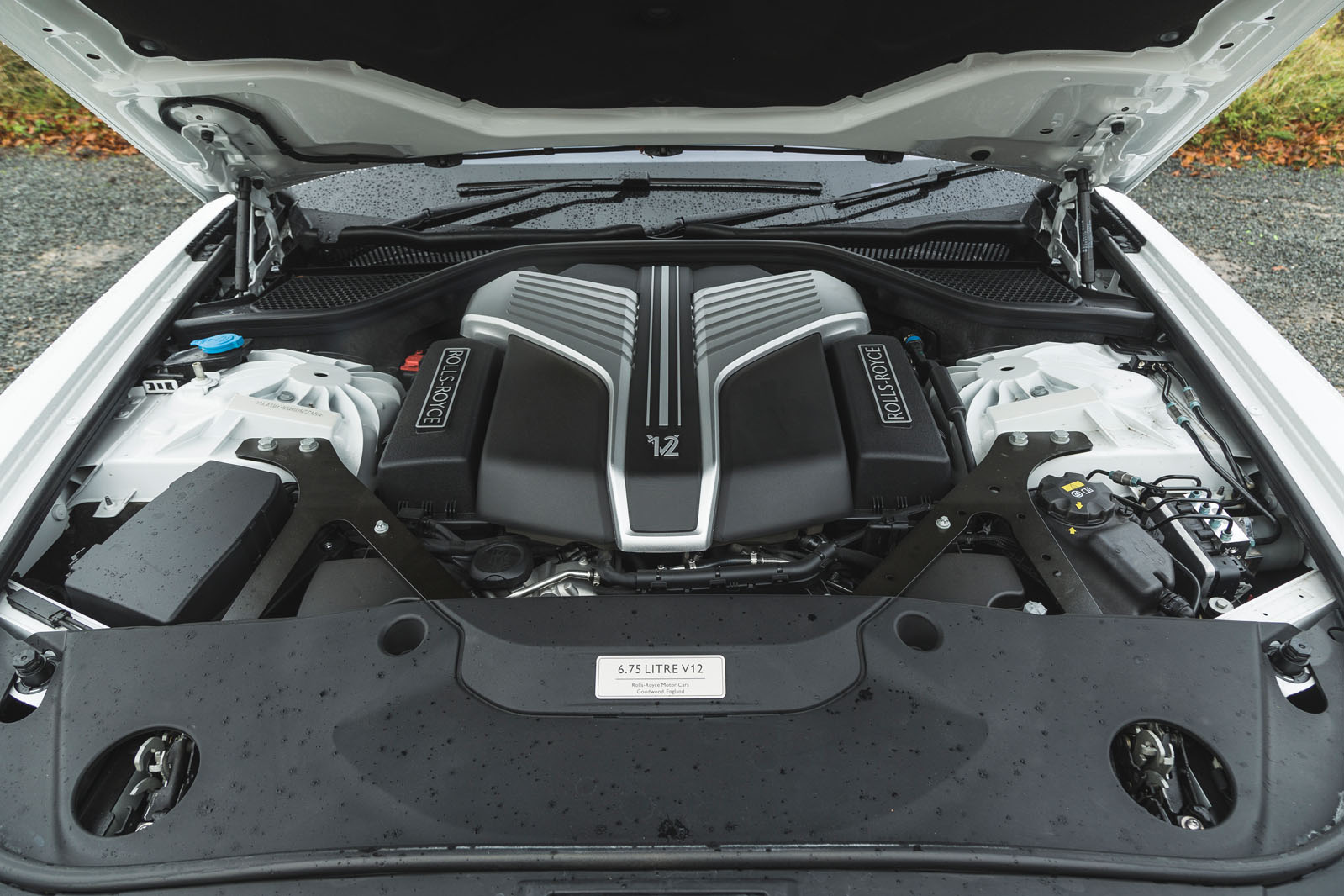

As with so many entities that appear to operate with effortless ease, there is plenty going on beneath the surface of the Ghost’s bodywork.

The work Rolls-Royce puts into its ‘Architecture of Luxury’ extends considerably further than the endless dimensions and localised stiffness, and the aluminium it uses takes more complex forms than necessary in order to quell as much road-generated resonance as possible. The bulkhead and floor are also double-skinned to sandwich damping felts, and overall more than 100kg of acoustic damping material is used. This includes the double-glazed windows and sponge within the Pirelli’s PNCS tyres.

No surprise, then, that the Ghost is sensationally quiet. At idle, the V12 is so well isolated that inside the cabin we registered just 40dB, which is quieter than ambient levels on a sleepy suburban street. At 70mph, that rises to a scant 58dB – comfortably less than the 64dB recorded by the Flying Spur and even the 60dB of the Rolls-Royce Phantom. This demonstrates that Rolls-Royce is making good progress even at the sharpest, most challenging and perhaps most expensive end of its development criteria.

The benefit for passengers is that boarding the Ghost and closing the vault-like doors seems to transport you to another dimension, where the outside world feels faintly abstract. It’s when you find your sleepy self sat in the back of the Ghost, in the outside lane of the motorway, listening to music with remarkable clarity, that you realise that intrinsic, bona fide ‘luxury’ can be every bit as thrilling and captivating as cornering at high g-forces in the latest supercar.

Ride quality, which benefits from Rolls’ mass dampers on the front axle, is familiar from the Phantom, in that the body is permitted to make languid long-wave movements, but not quite to the same extent. If there is a fly in this serene ointment, it concerns secondary ride, which is mostly excellent but can on occasion transmit the road surface fractionally too faithfully.