The Second World War saw the deployment of some bombers that were not just flawed but terrible.

Underpowered, unstable, poorly armed, or simply obsolete, these aircraft struggled to fulfil even the simplest of missions. This list examines ten of the worst bombers of the war — machines whose design failures made them as much a danger to their crews as to the enemy:

10: Tupolev TB 3

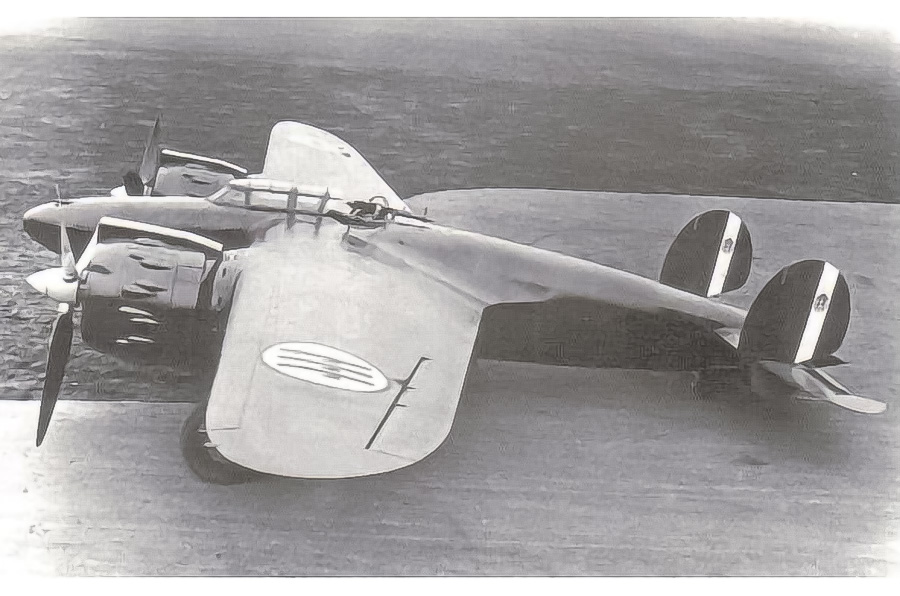

When the Soviet Tupolev TB 3 first flew on 22 December 1930, it was an impressively modern design. Unlike most aircraft of the time, including all operational heavy bombers, it featured a self-supporting, or cantilever, wing. This cleaner, stronger wing reduced drag and hinted at the future of aviation design.

For a bomber first flying in 1930, the TB-3 was unusually large, modern in its cantilever monoplane configuration, and unique in being powered by four engines. Revolutionary when it first arrived, it was dangerously outdated by 1941. Vast and lumbering, with a top speed of just 132 mph (212 km/h), it was a sitting duck against German fighters.

10: Tupolev TB 3

Soviet sources are vague and somewhat contradictory on loss rates, but known incidents, such as a river crossing raid in June 1941 - where multiple TB-3s were lost to enemy fighters - illustrate the dangers. The shift to night missions soon after also hints at the aircraft’s vulnerability during daylight operations.

Even in creative roles—transport, paratroop carrier, or “fighter mothership”—the TB 3’s performance remained dismal. Elite crews risked life on missions it was never suited for. The aircraft had no real place in a 1940s war and was finally retired in 1945, long after first being officially withdrawn from frontline service in 1939. Around 820 TB-3s were produced.

9: Blackburn Botha

The Blackburn company is always represented in any list of terrible aircraft, and so for the dignity of Blackburn fans, let’s get this out of the way first. The Botha first flew in 1938, entering service after the war had started, two weeks before Christmas in 1939.

Though the Botha is often described as underpowered, it is interesting to compare it to the Beaufort, which is not condemned in the same way. Even with a higher power-to-weight ratio on paper, the Botha’s draggy airframe and poor aerodynamics made it slower and less capable than the Beaufort. Its poor performance meant it was never to enter service in its primary role as a torpedo bomber.

9: Blackburn Botha

It also suffered from poor lateral stability, and though a slew of crashes followed, this was not unusual for a new type entering service in the late 1930s. Had that been all, it would have been nothing worse than an obscure mediocrity, but Blackburn had also made it extremely difficult to see out of the aircraft in any direction except dead ahead due to the position of the engines. This was an untenable failing for an aircraft now intended for reconnaissance, and the Botha was supplanted by the Avro Anson, which it had been supposed to replace.

Passed to training units, the Botha’s vicious handling traits conspired with its (effectively) underpowered nature to produce a fantastic number of accidents, yet somehow a terrifying 580 were built, and the type soldiered on until 1944. Though in its later service it was sensibly generally pushed into second line roles.

Add your comment