If you’ve never been to an engine factory, it might come as a surprise to find there are more multi-million pound machining systems than people: JLR’s brand-spanking new facility in Wolverhampton, the Engine Manufacturing Centre, is no exception.

In the machine shop at the 120-acre site close to the M54 motorway there are 180 cube-like boxes, each equipped with a robotic milling, grinding or drilling machine, all quietly humming away while being run by a staff of just 50.

The staff are probably humming away, too, comforted by the bright and clean, high-tech working environment. The bulk of the shop floor staff have never worked in a car plant or manufacturing, joining from all walks of life.

This is a green plant, too. As JLR’s overhead pics show, the roofs of the three main buildings are festooned with solar panels, generating a claimed 6MW of electricity, much of which is fed back into the national grid.

Reputedly, JLR also did a good deal on this huge greenfield site - just about the only one that was suitable and available post-2008 - when other industrial companies were cutting back on investment. Since then, investment has poured in and it is now in the middle of a £500m injection.

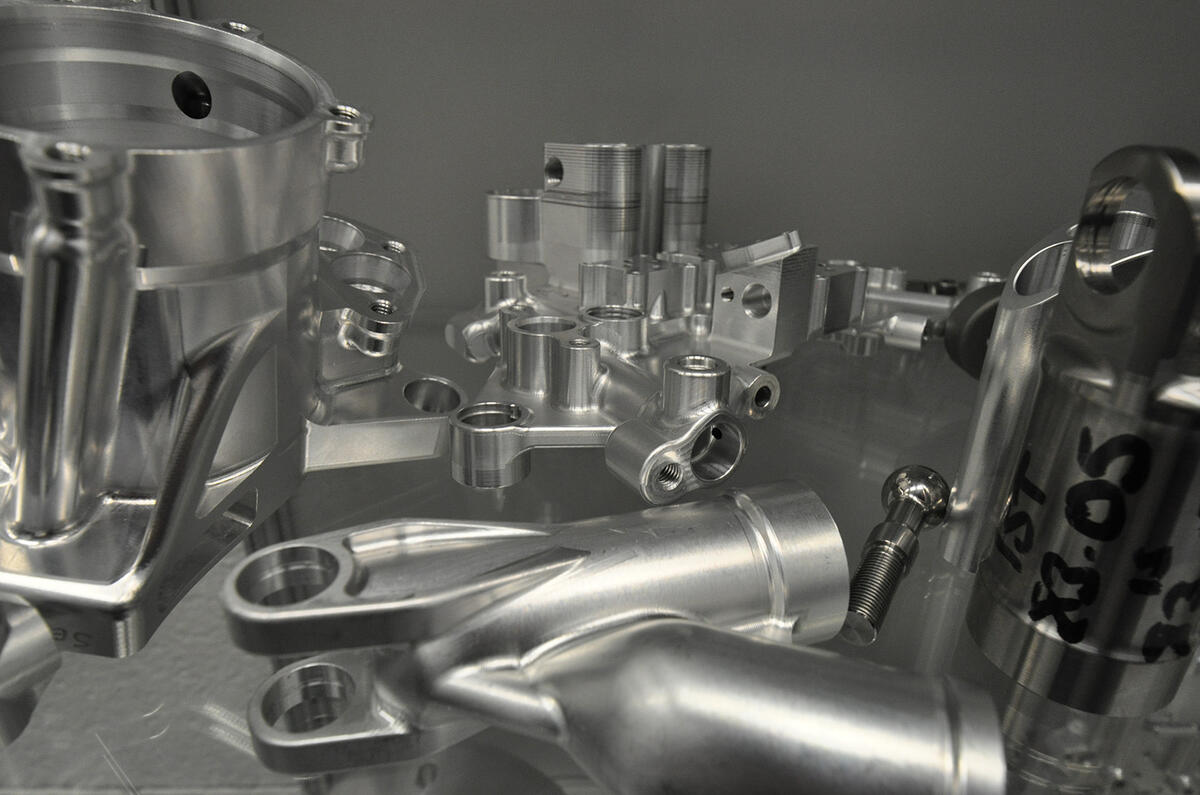

But the nitty-gritty of an engine plant is inside the sheds, where 100 top-end five-axis, computer controlled milling, grinding and polishing machines work their magic.

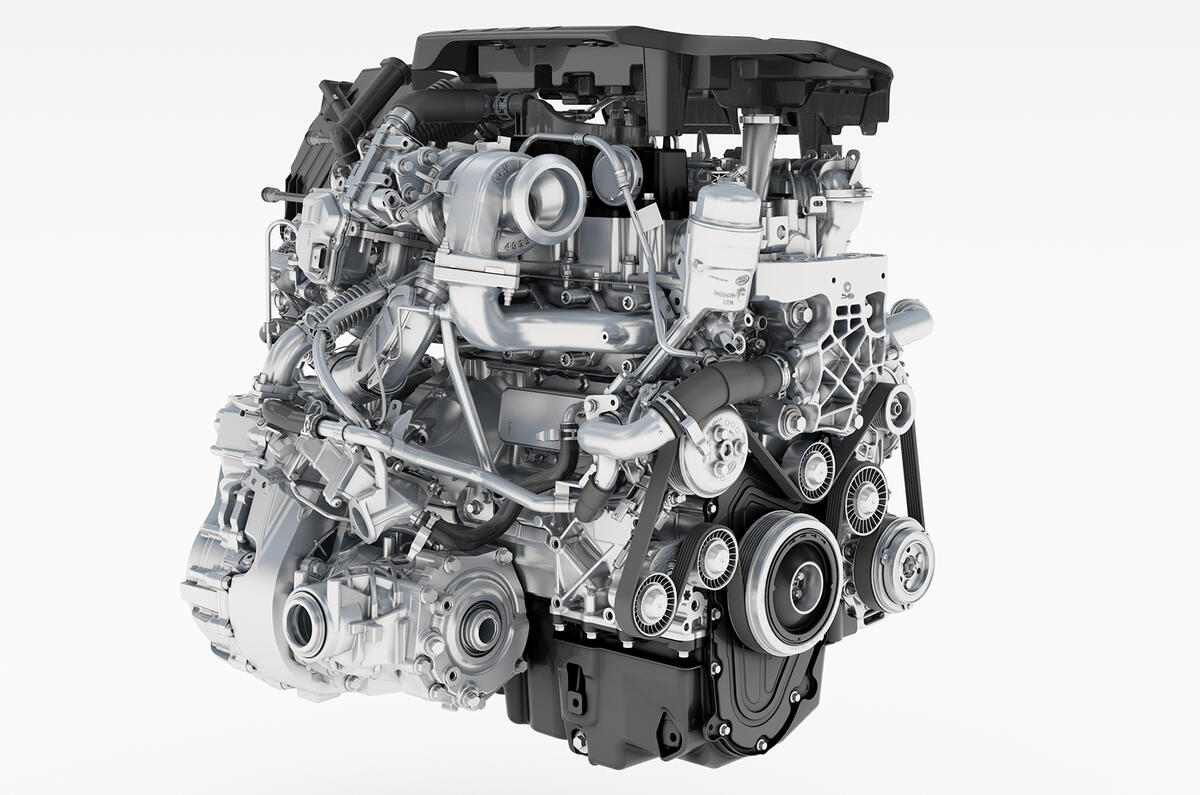

This technology-packed machining hall feeds alloy blocks and heads into two assembly lines for the Ingenium family of engines, which is currently limited to four-cylinder diesels, but is nearly ready to start pumping out four-cylinder petrols. The first 110g/km Ingegium AJ200 diesel rolled out last year.

Unfortunately on our press visit, news of the rumoured straight-six Ingenium is thin-on the ground.

But the machining shop is working hard, on two shifts, starting each day or night with part-machined, or ‘super-cubed’ blocks, heads and crankshaft forgings mostly supplied from German foundries. Super-cubing reduces the weight and volume of the block and head castings and crank forgings, making them cheaper to truck to the UK.

The complex oil pan casting has a simpler route to Wolverhampton, chugging up the M6 from Coventry.

The first step is to double-check that the castings are not porous and don’t suffer shrinkage – dimensional inaccuracy – before feeding them in to the machines where the intake ports, bearing faces and bores for the dry-liners are machined to accuracies of 3 microns – fractions of a millimetre. A human hair is 50 microns.

Final assembly is more labour intensive with 180 staff screwing, bolting and torquing the valve gear, induction and electrical gubbins together on an 850m long line, laid out in a W-pattern to maximise efficient use of space.

Join the debate

Add your comment

No foundries in Britain?

Yes ,City tiger is right. Has Britain lost the ability to actually make these items? Are there any foundries in the UK?

Is it actually possible that British management, over time, has thrown away the ability to actually make things?

Lots of engines!

Tack time?