If Ginetta had chosen 2017 for the debut of its all-new Le Mans car, instead of targeting next year’s event, it’s possible the Yorkshire sports car company could have scored an outright victory in the 24-hour race.

This year’s Le Mans race will go down in history as the one in which Porsche’s and Toyota’s fancied frontrunners faltered – arguably because of the over-complexity of their hybrid powertrains. An LMP2 car, theoretically much slower, came within an ace of defeating the race-winning Porsche. As it was, LMP2 entrants finished second through to seventh behind the 919 Hybrid.

Ginetta’s well advanced non-hybrid LMP1 car for 2018 probably wouldn’t have beaten this year’s class leaders at their best, perhaps, but it would certainly have had the legs of a bunch of LMP2s and probably the problem-struck winning Porsche, a fact not lost on Ginetta’s Le Mans-loving owner and leading light, Lawrence Tomlinson, whose own prolific racing career includes a Le Mans win in the GT2 category in 2006.

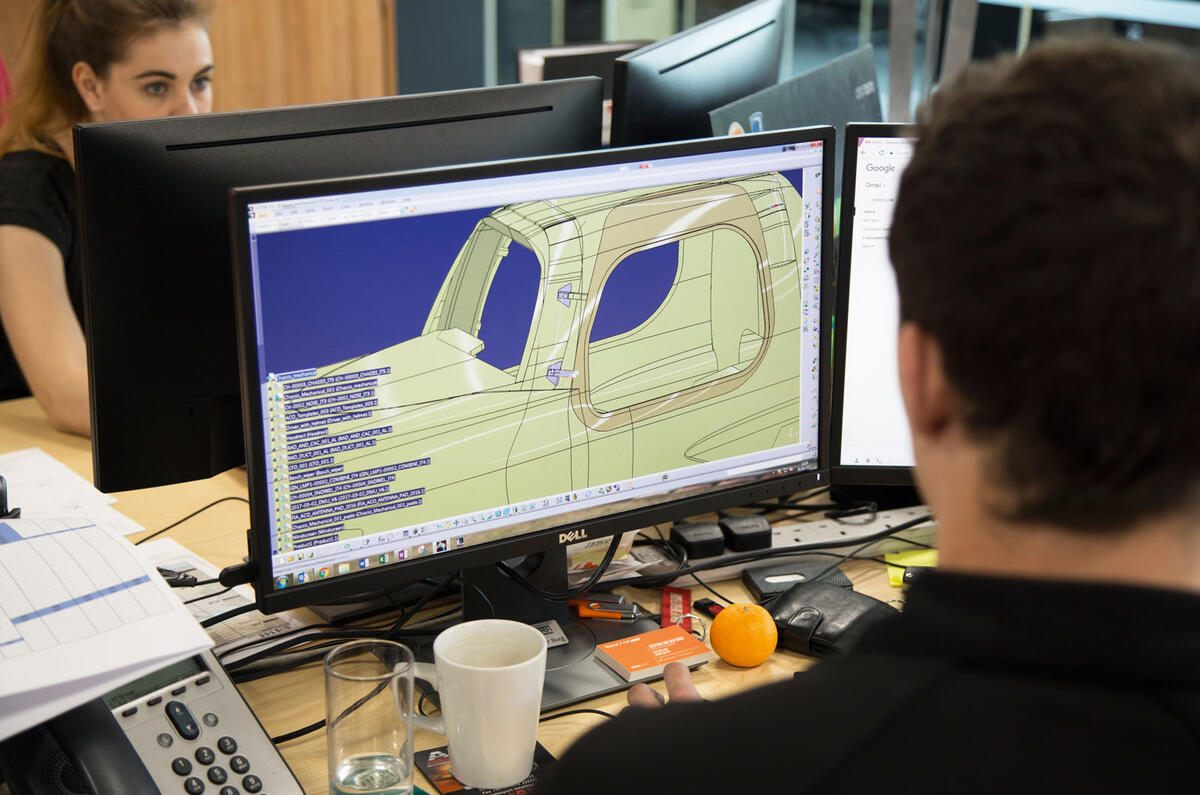

Nevertheless, Tomlinson, who, like most pundits, expects a fresh set of Le Mans regulations to be announced in 2020 for the 2022 racing season, reckons the stars have aligned for him. The new rules are likely to require hybrid powertrains and will probably be drafted to entice Peugeot back to La Sarthe, but in the meantime there’s an opportunity for the go-getters from Yorkshire. They’ve already completed encouraging tests

of their Mechachrome-powered car in the Williams wind tunnel, and are well advanced with attracting customer teams to race it.

This is big stuff for a company that for the

past 59 years has made its living providing simple, enjoyable front-engined race cars for almost everyone, from talented 14-year olds to professionals who need the power of a Chevy V8. Right now, Ginetta runs no fewer than five highly successful championships of its own.

Tomlinson grew up in Batley, West Yorkshire, and trained as an engineer straight from

school, but his career has since been directed

by dominating themes: an abiding love of cars (and latterly helicopters) and an entrepreneurial spirit that drove him, at the age of 23, to borrow £500,000 from the local bank and buy his parents out of a care home they owned.

He soon turned that into a network of homes, selling some and keeping others, and established parallel construction and software businesses to help them run better. By 2011, the Sunday Times estimated his net worth at £550 million.

However, there’s much more to Tomlinson than money. Entrepreneurial skills, for one thing: he has a string of honorary doctorates for his achievements in industry. Political awareness is another trait: he was Entrepreneur in Residence in the Department for Business, Innovation and Skills in 2013-14, working to help embryo businesses by removing red tape and boosting growth. He also created an almighty stink over banks’ treatment of small companies during the recession and it is work that continues today.

Despite all this activity, Tomlinson has always found time to run a career as a successful race driver, usually racing TVRs until he bought Ginetta in 2005. In the beginning, Tomlinson’s plan was to buy TVR itself. He and TVR’s then-owner Peter Wheeler were close to a deal until so-called Russian mini-oligarch Nikolai Smolenski arrived, figuratively speaking, with a suitcase full of money. “I thought Peter and I had an understanding,” says Tomlinson. “You know a deal between Yorkshiremen is good when both parties are equally unhappy.”

Tomlinson regards what subsequently happened in Blackpool as horrific: “We went from having

a struggling company – but which had a future

– to a situation where every job was lost. A whole skill base in the North West was destroyed. But in fairness to Nikolai, he was only 23 or 24, operating in a foreign country, and he was allowed to buy a car company. You didn’t have to be a genius to see what was going to happen.”

Tomlinson reckons he “could have done something with TVR”, but also feels the failure of his deal with Wheeler was something of a blessing. “It was good not to have any of the legacy issues. Ginetta was a blank canvas,” he says.

One of the best things about the Leeds-based firm, he says, was its Ginetta Junior race series. Started in 2003, and a regular fixture on the undercard of the Dunlop MSA British Touring Car Championship, it has proven consistently attractive to young drivers and largely responsible for the company’s “small profit”.

Looking back to 2005 at his aspirations for Ginetta, Tomlinson agrees he’s “a bit behind” where he’d have liked to be but notes that the company has coped with the biggest depression since the 1920s. “But we’ve kept building cars and filling grids,” he says, “which I see as a fine achievement by the whole Ginetta team.”

Tomlinson greatly values old-school driver skill, one reason he has little time for powerful cars bristling with electronic driver aids. He believes they dull the driver experience in racing: “You get the professional and the gentleman driver braking at exactly the same spot; there’s no skill in it. The same goes for traction controls and torque vectoring. You might as well do what [developing autonomous car racing series] Roborace does, and let the cars race themselves.”

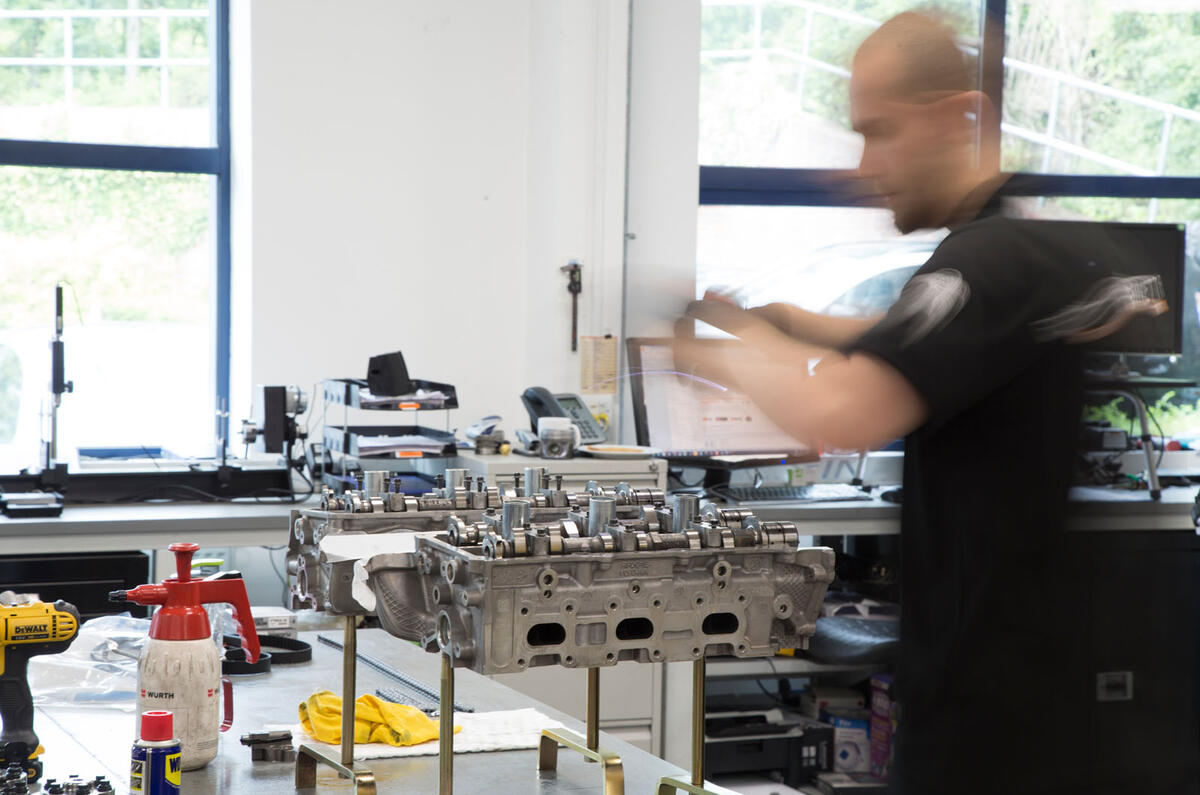

Ginetta people talk about building road cars, but a visit to the modern factory, east of Leeds where the M1 and A1(M) motorways meet, soon shows that the emphasis is on racing cars, some of which can be registered for the road. Annual production of the company’s road and race cars used to be 200; now it’s 120 to 150, all hand-built, because though the entry-level cars are very affordable, top-end models can be £200k-plus.

In 2011, Ginetta bought and expensively re-engineered what it now calls the Ginetta

G60 (previously known as the Farbio GTS), but despite positive reviews and a handsome skin, it has had little success with buyers. The road car business still interests Tomlinson because he’s an enterprising, competitive sort of bloke and can see how well other UK car companies with ‘heritage’ names have been doing.

“We’ve not really worked at this yet,” he says, “and we have no concrete plans to announce,

but we’re definitely interested in the road car space. The big trick is to decide what it is people want, because many wouldn’t know if you asked them.” For the time being, Tomlinson is gathering information by driving and critiquing some of the road cars the market likes most. If Ginetta were to build a specialist road car, it would be light, agile, uncomplicated and uncompromisingly good fun to drive. That last characteristic, he insists, would be its most important of them all.

Target: Le Mans glory

Ginetta’s all-new LMP1 car, Britain’s hope for an outright victory in the 2018 Le Mans 24 Hours, remains on course for first track tests in October, according to Tomlinson.

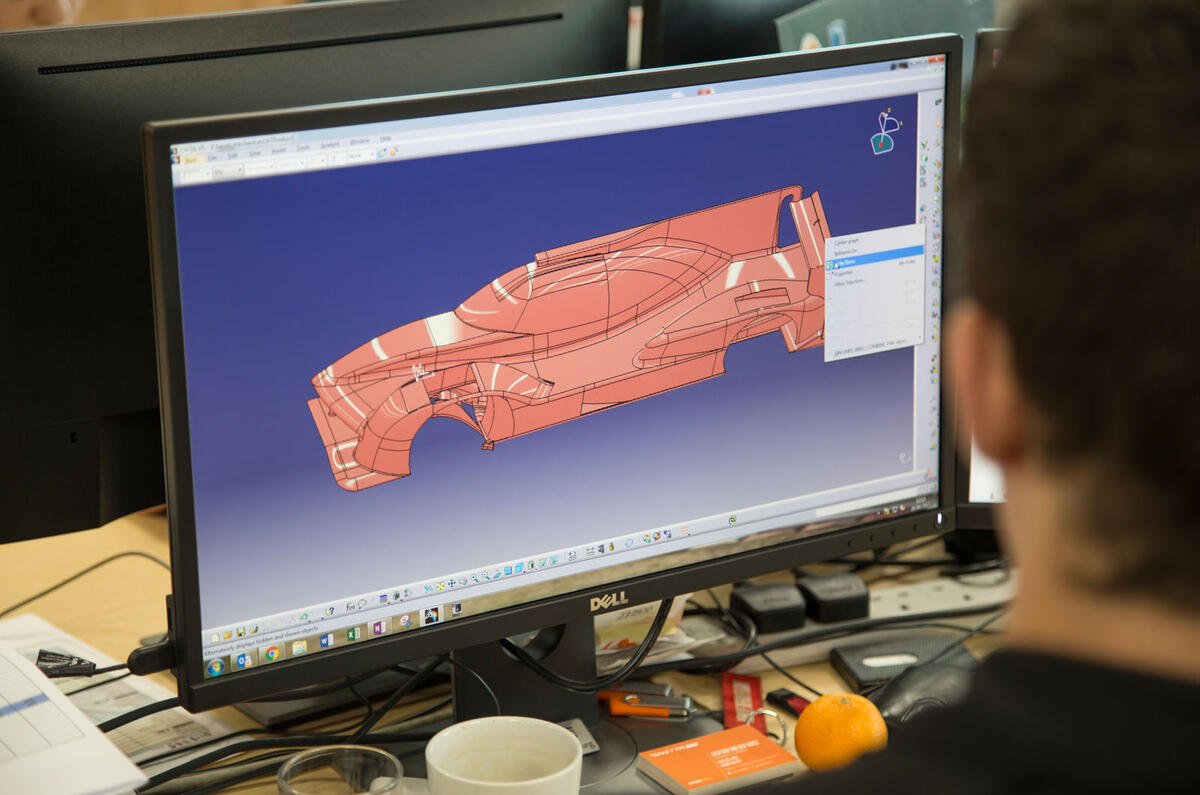

The car, recently described as “the world’s fastest customer car”, is an all-carbonfibre design that combines the efforts of Ginetta’s own Leeds-based designers with input from Williams Advanced Engineering (wind tunnel testing) and Adrian Reynard (CFD). According to current plans, three two-car privateer teams of LMP1 Ginettas could make it to next year’s grid.

The Ginetta effort is part of Tomlinson’s plan to simplify competition in the top category. While others have benefited from the speed

of hybrid powertrains, but suffered from their complexity, Ginetta will use an 800bhp version of Mechachrome’s 3.4-litre V6, which has been honed in international open-wheeler racing.

Related stories:

Add your comment