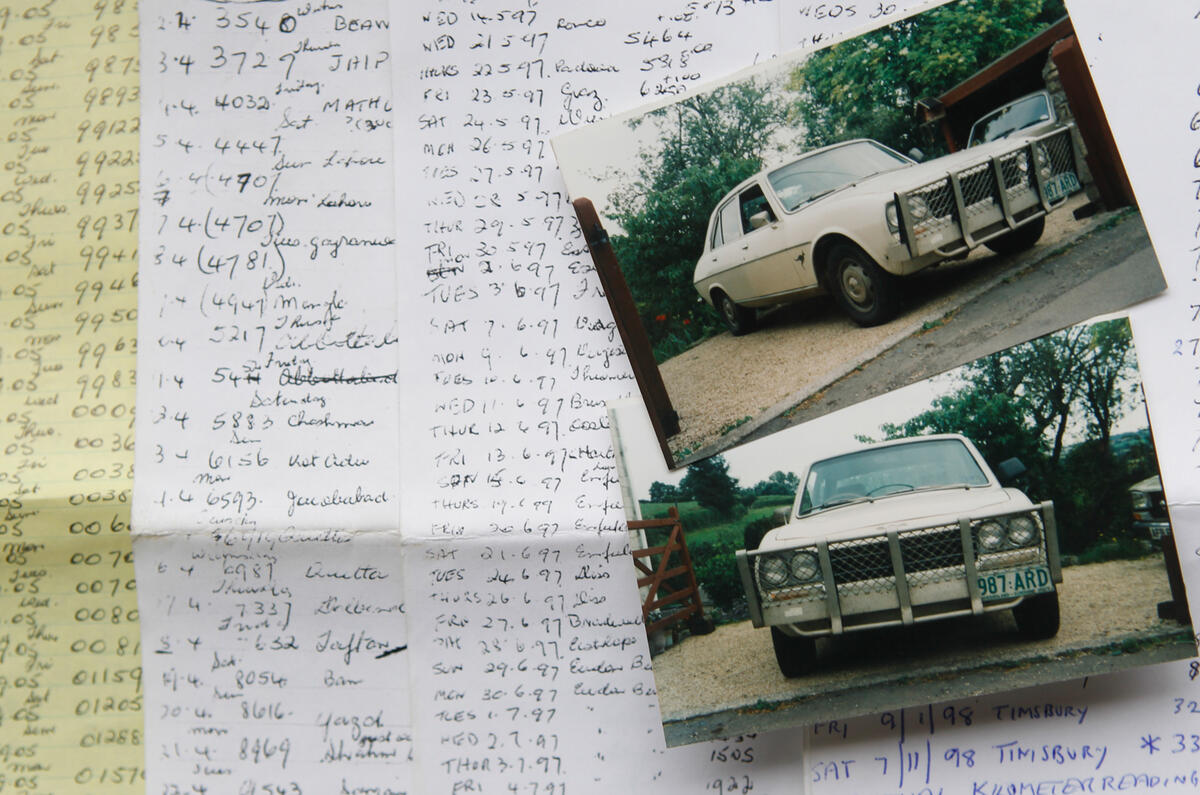

Were Keith Herbert’s Peugeot 504 an ordinary car, it would have been scrapped 15 years and half a million miles ago.

It certainly wouldn’t be living in a warm Wiltshire garage as it does today, still in daily use but fêted for having covered more than a million kilometres (625,000 miles) in a globetrotting life of drama and adventure.

As the most recent of the car’s five owners, Peugeot lover Keith Herbert, a retired haulage boss who lives near Bath, has ‘only’ owned the car for the past 15 years, storing it alongside four other Peugeots. During that time, he has added a ‘modest’ 100,000km but, most important, he has had the distinction of turning up the magic million on its kilometre-reading odometer.

The famous 504 started life in a Renault-owned assembly plant in Melbourne, Australia, under a curious colonial deal struck between the French automotive rivals that led to 504s being built alongside Renault’s own R12s and R16s. This 504, a 2.3-litre GLD diesel with a four-speed gearbox, was delivered to its first owner 1500 miles away in Brisbane, on the Queensland coast.

From the beginning, it was driven hard. Three give-no-quarter owners put 300,000 miles on the car in its first nine years, which would have been enough to bring most cars to their knees. Not the 504. “At that stage,” says Herbert, “the car was acquired by the bloke who eventually sold it to me, an Australian farmer who had emigrated from Ireland called Graham Smith. He overhauled the engine – and then the hard part of its life began.”

Smith loved travelling, and the car he most loved driving was this china-white, Melbourne-made 504, its engine now rejuvenated.

Between 1988 and 1996 the car was driven almost non-stop in Queensland’s ‘unimproved’ outback, where roads were usually rutted, corrugated and covered in loose stones that put the windscreen at risk. A particular problem was ‘bulldust’, a notorious airborne form of red dirt that can bypass even the best door seals.

For much of this time the 504 was used by Smith’s daughter, whose job as a relief teacher at various far-flung native Australian settlements took her on 1000-mile journeys in temperatures beyond 40 degrees.

These were tough and risky conditions for anyone driving alone, Smith recalls, but the combination of the Flying Doctor and the renowned Australian ‘bush telegraph’ kept her safe. And the car never failed to proceed. When Smith’s daughter stopped using the 504, it was taken over by her husband, a noted leadfoot, who pushed it to the limit.

Throw in a few of Smith’s own 3000-mile round trips and it’s no wonder that 140,000 miles further on – and with the odometer reading an amazing 880,000km (550,000 miles) – the 504 needed more refurbishment: new rings and bearings, a new timing chain, a secondhand cylinder head, new gearbox seals, a differential rebuild, new suspension bushes and a brake overhaul.

Why did these people persist with this 504, which was now very old in most people’s terms? The answer is simple: early in its life, the 504 acquired a legendary reputation for ruggedness and reliability; this one was still too good to throw away.

As Herbert notes, in their heyday 504s sold in reasonable numbers in the UK, but they are rare here today because in older age, after a life of comparatively light duty, most were bought up and shipped to Africa, to live again in tougher conditions.

Join the debate

Add your comment

If you like to ride more than

If you like to ride more than 500 000 km.

There are other cars :

- Volvo P1800.

- Renault 21 (Turbo)Diesel.

The 504. An enviable

The 504.

An enviable reputation of reliability.

For a long time used in Africa.

It's the same for the 404.

President Ahmedinejad (Nobel

President Ahmedinejad (Nobel Peace prize), auctioned off his 504, and the final bid was a reported $2.5 million. wikipedia. Pininfarina styling, and assembled in over 10 countries, upto 2005.

kcrally wrote:

Why mention Nobel Peace Prize in this context?.