Turning left through the ancient gap in the Members’ Banking then bumping your way downhill over the lumpy concrete of the old Campbell Circuit into Brooklands Museum’s estate, it’s difficult to know whether one should feel reassured or overawed.

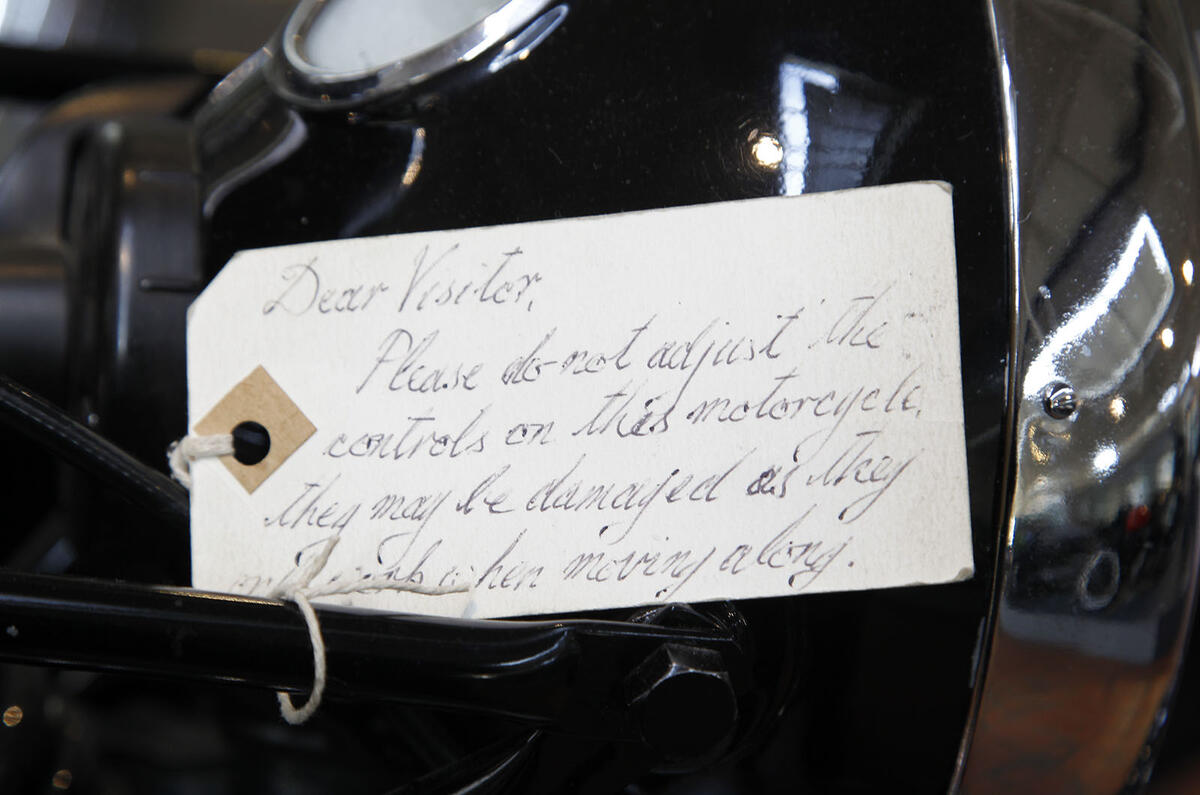

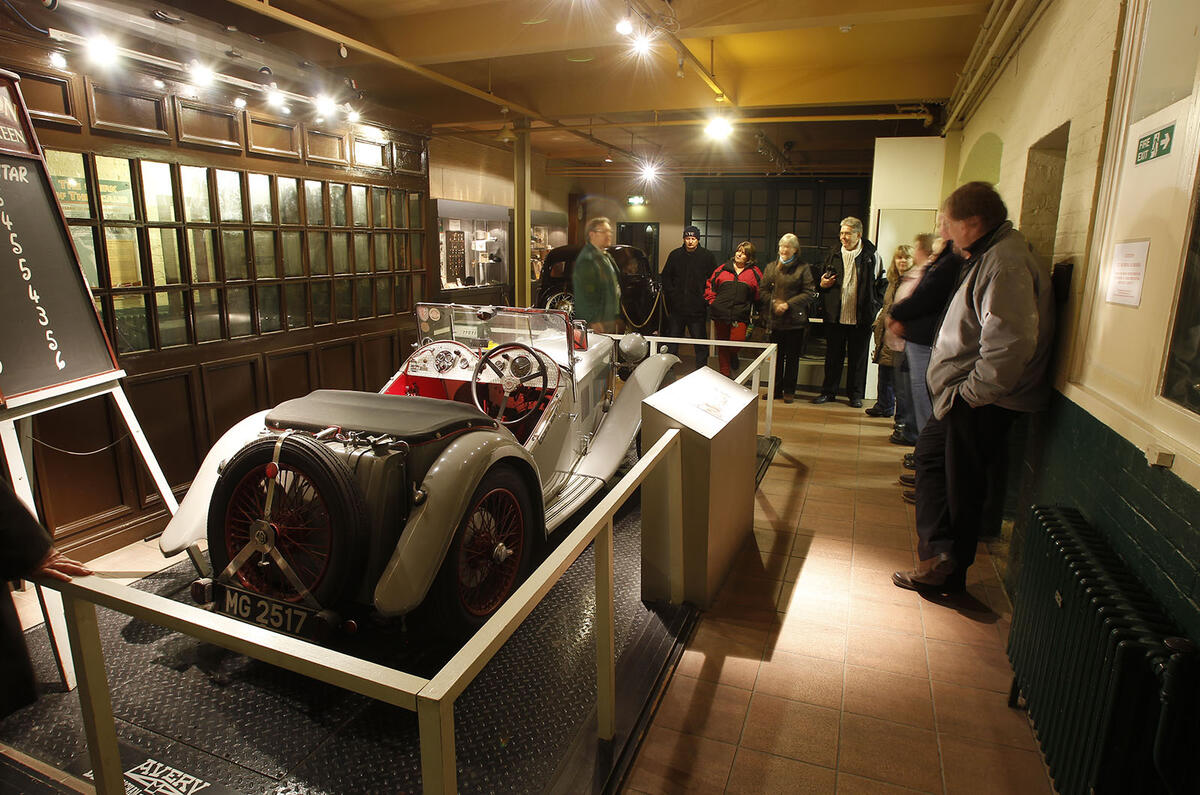

On one hand, Brooklands has always had a homely, welcoming quality, and that goes double nowadays. After an uncertain half century its existence is no longer under threat. It earns a handsome keep and is run by an ambitious management with many achievements to its credit and even bigger preservation plans to come. Still, there’s a comfortable lack of pretension about the old place.

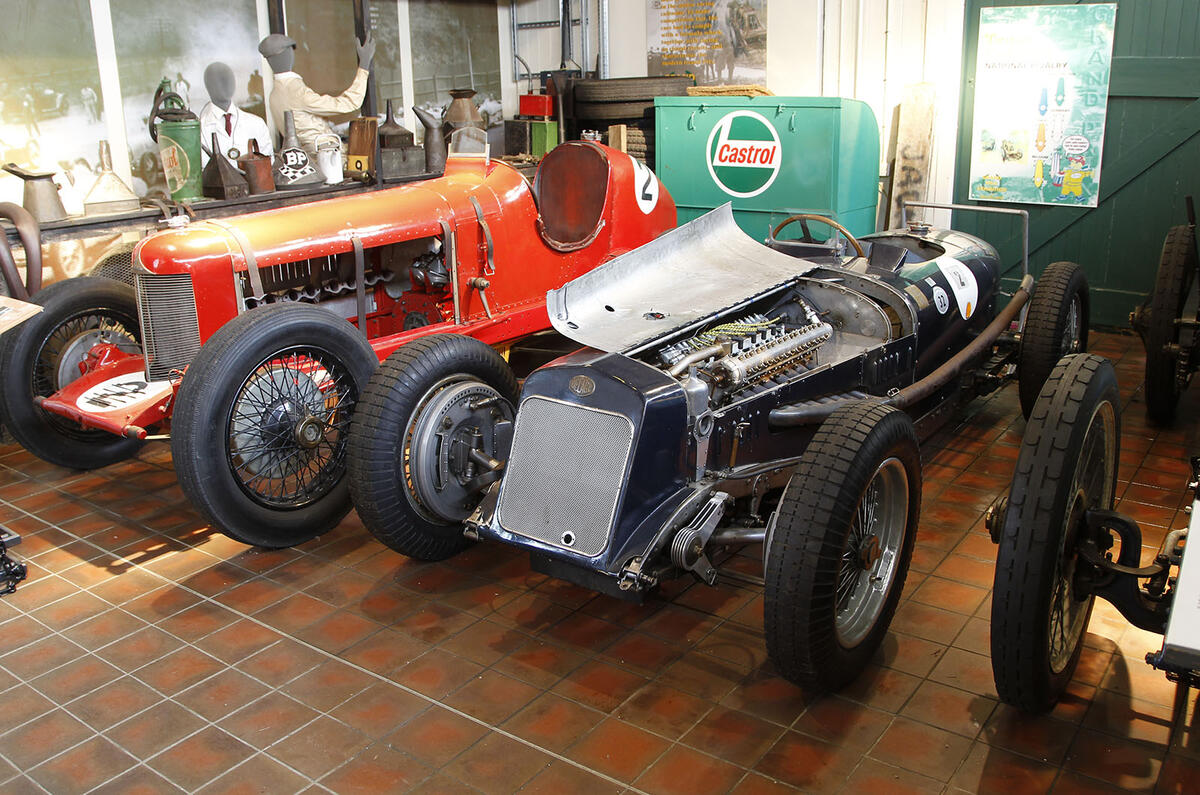

Yet on the other hand Brooklands remains one of the true wonders of the world. Within its original 330-acre boundary, many of Britain’s earliest motoring, motor racing and aircraft businesses were born. Between the wars it was the undisputed cradle of British motorsport and car development, creating the culture that led to Britain’s modern-day pre-eminence in motorsport.

By the late 1930s, Brooklands was building the aircraft that would win the Battle of Britain and spearhead Europe’s liberation. And for 40 years after that it served as a manufacturing site for Britain’s airliners, ‘V’ bombers and Concorde, the world’s one and only successful supersonic airliner. This is sacred ground.

The genesis of everything was one individual’s extraordinary decision in 1906 to build an enormous banked circuit in semi-rural Surrey, like nothing that had ever existed. In just nine months, 1500 workmen created the world’s first purpose-built racetrack.

It was active between 1907 and 1939 but large parts of it still exist today, along with many of the most important buildings. Together, they create an aura so special that when we decided to begin a year-long series about Europe’s ‘living’ automobile museums, there was simply no case for starting anywhere else.

Brooklands’ creator, Hugh Fortescue Locke King, was a patriot to the core. Visiting the 1905 Coppa Florio races, near Brescia, he was surprised at the lack of British-made entries, then concerned to hear from competitors that the development of cars in his homeland was stunted by a 20mph national speed limit and the lack of any place to develop their performance.

He proposed a flat track on a bowl of marshy land spanning the River Wey beside the London to Basingstoke line, but the project soon fell into the hands of an ambitious army engineer who embellished the plan to create a bean-shaped, 2.75-mile oval track, with banked walls nearly 30ft high at each end so cars could corner at 120mph.

The project cost £150,000 – an amount so huge that Locke King was almost bankrupted. Brooklands was amazing but it wasn’t perfect: from the first day of racing its new-fangled reinforced concrete began to crack (it would always need much winter maintenance) and early crowds were disappointing. But it had an instant positive influence on the creators of the Indianapolis ‘Brickyard’.

When racing began, so little had been decided about the new sport’s rules that the organisers borrowed extensively from horse racing. Drivers raced in owners’ colours (car numbers came soon after, once it was noted that silks were invisible at speed), and it was Brooklands that enshrined the idea of a ‘paddock’ being a parking place for competing cars, and a ‘clerk of the course’ as the manager of a race meeting.

Join the debate

Add your comment

I liked it too! I was well

Brooklands

Brilliant article Steve