The Aston Martin Vulcan was named after the bomber, not the Star Trek species, apparently. Which makes sense.

One was conceived to be noisy, obviously threatening, heinously expensive and limited in production and was destined to spend most of its time ready to run but actually mostly sat idle. The other one majors on logic.

And whichever way you look at it, there’s nothing terribly logical about an 820bhp 7.0-litre V12-powered car that you can drive only on track days that have remarkably liberal noise limits. The Vulcan measures at 118dB when its exhaust is in angry mode but can be reduced to 103dB with optional baffles in place. For a while, anyway. It fairly quickly destroys them and blows clean out through the exhaust, whereupon it becomes noisy again. The Vulcan is an insatiable kind of car.

Aston is establishing a new way of doing business that sounds comfortably organised but, when you meet people who work there, spells out very little rest at all. There’s one full new model a year – this year’s is the DB11 – which is then supplemented by a number (probably two per annum but perhaps more) of limited-run specials, such as this Vulcan, a special car even by the standards of special cars.

One reason it’s doing them is because Aston Martin’s boss, Andy Palmer, is rather keen to see his company making money – which would be something of a novelty – and the cashflow that the special projects bring in is the kind that is well worth having. The other reason is that… well, just look at it and imagine what it does for Aston’s status as a maker of sports cars.

There will be 24 of these Vulcans, each priced at £1.5 million plus local taxes. And although £36m wouldn’t cover Audi’s annual biscuit budget, it’s the kind of revenue that’s useful to a company the size of Aston Martin. There will be ongoing revenue, too. All 24 cars are sold (there were 24 because of Aston’s successful history at the Le Mans 24 Hours), but Aston will continue to look after most of them. It’ll maintain and service them, prepare them for track use and run a series of events every year where owners can come and drive, be tutored and so on. Aston will train your technician if you’re so inclined, so you can take your Vulcan home, or put it on a plinth and look at it.

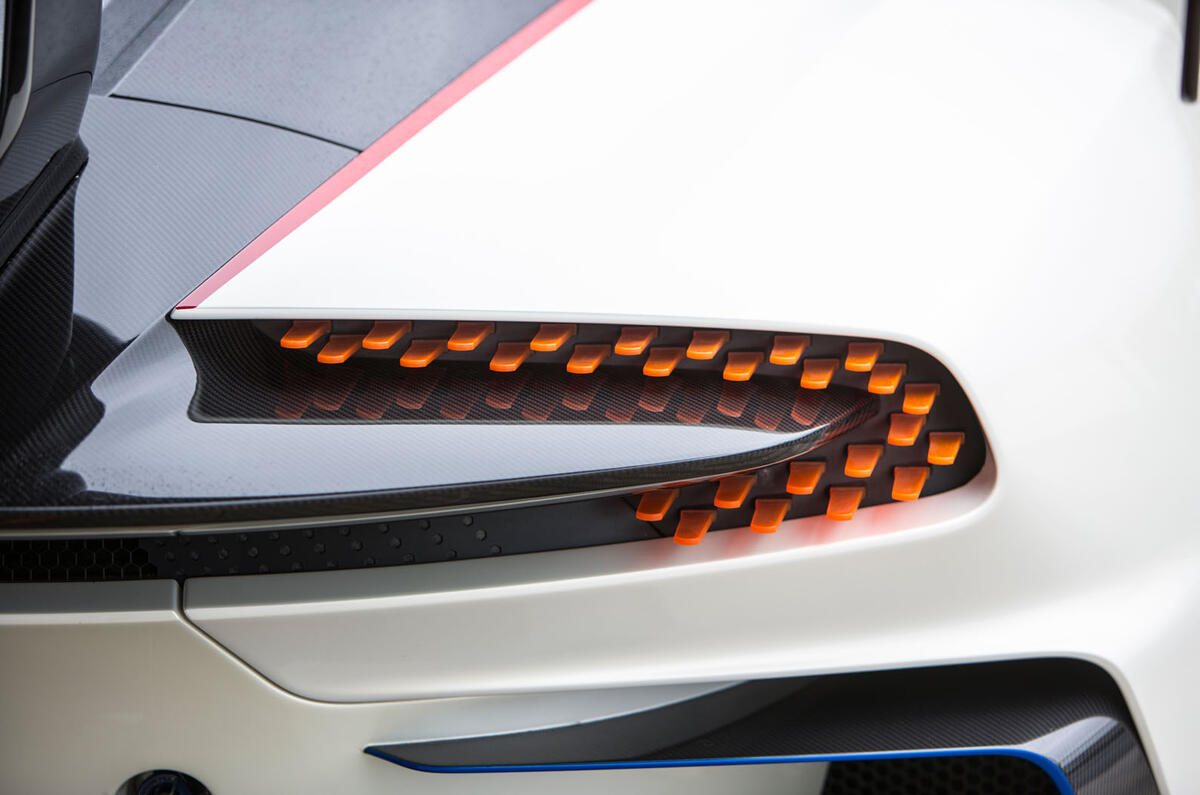

There are reasons why you might do that. I’m not convinced the Vulcan is a beautiful car, but I’m not sure it was meant to be. It is a striking one and, better than that, is exquisitely finished, inside and out. There is a certain race-car feel to the Vulcan, which I’ll come to in a moment, but in terms of its finish – each rear light is like 100 plastic lollipop sticks carefully inserted into the back of the car – it has all the hallmarks of a concept car.

Join the debate

Add your comment

Matt, it is simply untrue

I don't get this car

Flat out?