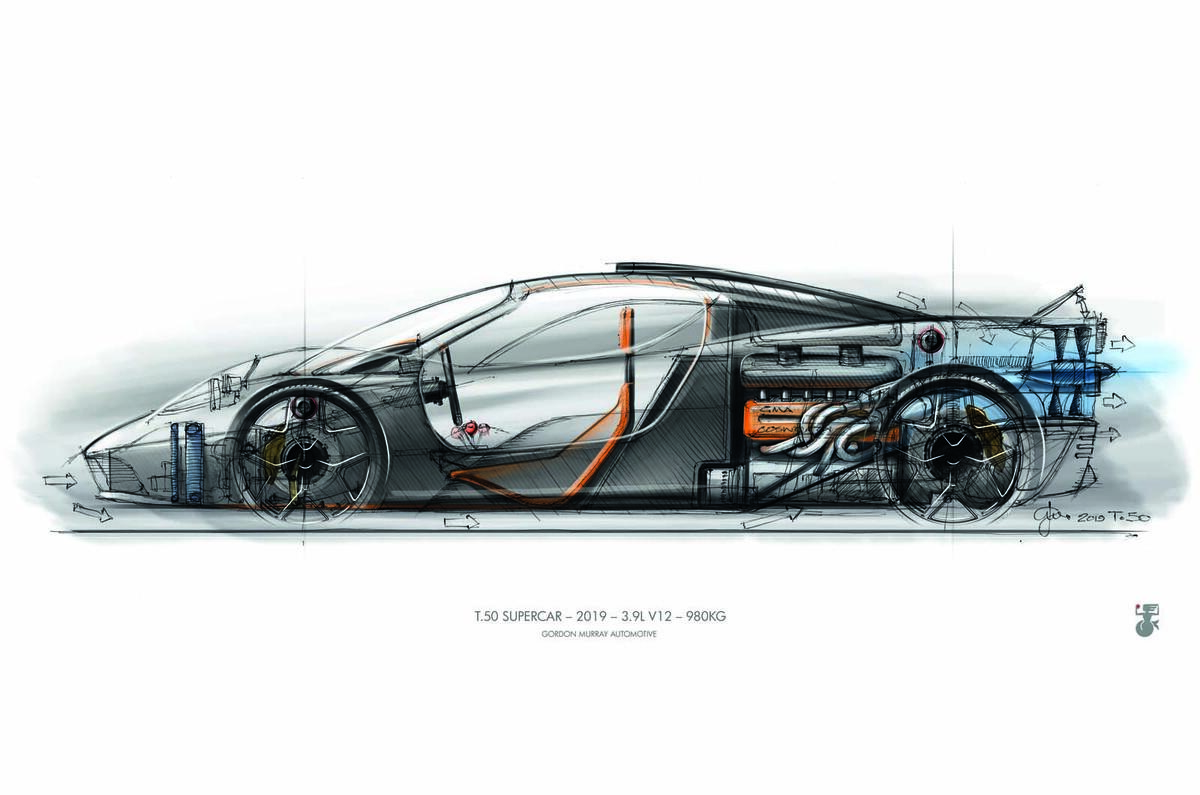

Someone posed the question the other day whether Gordon Murray’s new McLaren F1 successor, the T50, was a step backwards to simpler times.

In fact, the new supercar achieves the objective of high efficiency in every department without resorting to complex technology but by returning to basic principles. The T50 is so light, at 980kg, that Murray can get away with a naturally aspirated engine without being forced to use turbochargers and downsizing for efficiency reasons. The weight saving triggers the virtuous circle that is generally so elusive because the spiralling size and weight of cars usually prevents it.

UPDATED: The 650bhp T50 has now been fully revealed

Murray’s bespoke 3.9-litre V12 engine needs less low-down torque than it would for a much heavier car so the focus can be on power. Power is essentially torque multiplied by engine revs. Up to a point, the faster an engine goes, the more torque-generating combustion events happen per minute, so the engine does more work. The T50 engine revs to more than 12,000rpm, said to be the highest revving to date in a production car, and on the way will peak at 641bhp. The engine will have variable valve timing (VVT) to overcome the problem all combustion engines have of working well at both low and high revs. Most modern engines have it, but it’s essential if very high-performance engines like this are to remain drivable at all speeds.

Valves are opened and closed by camshafts – shafts running at half engine speed – with carefully shaped knobs set along the length (cams), one for each valve. The shape or ‘profile’ of the cams controls how much a valve opens, at what rate (suddenly or more slowly) and, crucially, when it starts to open and close. By opening valves for longer, there’s time to get more fuel and air in and exhaust out at high revs, where the big horsepower lives. The problem is that at low revs, the engine won’t run properly, because with so much time on its hands, fuel and air goes in one end and straight out of the other. Time is of the essence for a combustion engine: time to draw air into a cylinder, time to mix the fuel with the air and, surprisingly, the time it takes for the fuel to burn completely in the combustion chamber. That part might seem instantaneous but it isn’t. Petrol engine combustion is a fire, not a detonation.

It was virtually impossible to have the best of both worlds until the arrival of Honda’s VTEC system, which switches between two different camshaft profiles, for high-revving power and low-down flexibility. The simplest and most common form of VVT is cam phasing, which progressively rotates a camshaft forwards or backwards in relation to the crankshaft, varying the timing of valves opening and closing but not the amount the valves open (valve lift). Exactly what sort of VVT the T50 engine has is yet to be revealed, but whatever system it uses, it will exploit the basic need for VVT to achieve a successful marriage between drivability and outright, brutal power.

A 1960s masterpiece

Join the debate

Add your comment

Problem is...

After reading about the technical points of the new mega expensive bespoke V12 engine I lusted after the V8 Cosworth.